Usage of e-textiles-based sensors and actuators for various applications is gaining popularity in the wearable market owing to their ‘next to skin’ feeling. However, the majority of such products are found to be dependent on external sources of power. This not only adds to design complexity but also to other sustainability concerns. Carbon footprint of an AA battery is approximately 0.107 kilogram of CO2 equivalent.

Presently, almost all the commercial products existing in smart wearable market rely on external power sources in the form of conventional batteries either for one time usage or rechargeable. As per a study conducted by Swedish Environmental Research Agency, each kilowatt hour of batteries produced generate an equivalent of 150 to 200 kilograms of CO2. To make them self-powered, textiles are being designed as power generators to be integrated within the micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS). There has been extensive ongoing research to utilise energy harvesting and storing capabilities of textiles in various forms. While researchers, industrialists, designers and engineers are still struggling to come up with e-textile wearables enabled with reliability, reproducibility, repeatability and scalability for sensing and actuation, exploring energy harvesting and storing capability of textiles has also been of focus lately. This article briefly touches upon a few examples of textile-based energy harvesters.

There are more than one ways to harvest energy using textiles owing to few of their intrinsic characteristics and few others attained through finishes or structural arrangement in an ensemble. Textile-based energy harvesters are required to generate electrical power from textiles by harnessing various sources of energy. There are four popular methods for doing this which are – Piezoelectricity, Triboelectricity, Photovoltaics and Thermoelectricity.

Piezoelectric materials can be woven into fabrics to generate electricity when they are stretched or deformed. Triboelectricity property enables generating electric charge through contact and separation of two materials with different electrostatic properties. Photovoltaic textiles use solar cells to convert sunlight into electricity. For example, solar panels or cells can be integrated into textiles, such as clothing or outdoor fabrics, to capture solar energy. Thermoelectricity leads to generation of electricity in material when there is a temperature gradient across them. Textiles can be embedded with thermoelectric materials that can harness the temperature difference between the body and the environment, converting it into electricity. These power sources are integrated with e-textiles in miniature form factor to be a part of the MEMS, thus called as nano generators. One of them based on the principle of piezoelectricity are called Piezoelectric Nanogenerators (PENGs) and the other based on the principle of triboelectricity are called Triboelectric Nanogenerators (TENGs). They are also broadly called as Piezoelectric Generators (PEG) and Triboelectric Generators (TEG). PEGs and TEGs have been used in design and development of many upcoming self-powered smart wearables.

The above discussed energy harvesters utilise renewable sources of energy, thus providing a sustainable form of power source. For example, body movement, heat and biochemical potential are all readily available and easily accessible energy sources for wearable devices. A human being performs several tasks throughout the day leading to several voluntary and involuntary motions, which in turn generates energy and can be captured for power generation by these energy harvesters. Table 1 states the amount of energy generated by different body parts of a human being while walking, taking into assumption a person weighing 80 kg and walking at a speed of 4 km/ hour.

| A human being performs several tasks throughout the day leading to several voluntary and involuntary motions, which in turn generates energy and can be captured for power generation by these energy harvesters. The below given table states the amount of energy generated by different body parts of a human being while walking, taking into assumption a person weighing 80 kg and walking at a speed of 4 km/ hour. |

Table 1: Energy generated by different body parts during walking

| Body parts | Power (in watts) |

| Shoulder | 1.34 |

| Elbow | 0.78 |

| Hip | 7.2 |

| Ankle | 18.9 |

| Heel Strike | 1-10 |

| Knee | 33.5 |

This article endeavours to cover the design and development aspects of PEGs and TEGs. Figure 1 is a schematic representation of energy harvesting through piezoelectricity in a textile based-ensemble. In this particular case, stress (pressing) as a mechanical force has been utilised for electron flow.

Figure 1: Principle of piezoelectric energy harvesting

Various designs have been suggested for PENGs that meet the desired level of miniaturisation for smart textiles and the actuation capabilities associated with human motion. As an example, a hybrid configuration of piezoelectric fibres was created by aligning BaTiO3 nanowires with polyvinyl chloride (PVC) polymer. These fibres were incorporated into a plain weave fabric in the warp direction, while copper wires and cotton yarns served as electrodes and insulating spacers in the weft direction, respectively. When employed in an elbow band, this set-up produced voltages approaching 2V and an output power of 10 nW.

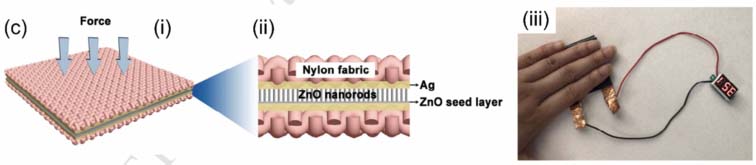

Similarly, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) electrospun nanofibres were utilised to engineer yarns through twisting and plying, which were then woven into fabrics. This approach achieved a voltage output of 2.5 V under a 280 mN force. Exploring another avenue, ZnO nanorods patterned on textiles were investigated for the development of textile-based PENGs. A uniform array of densely packed, vertically arranged ZnO nanorods on the silver-coated surface of a nylon woven fabric was developed to act as one of the PENG electrodes. Another piece of the same fabric, featuring a screen-printed silver coating, served as the counter electrode to form the sandwich structure. Power outputs of 80 nW and 4 nW were achieved through palm clapping and finger bending, respectively. Notably, foot-stepping actuation lit several light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Examples of PEG ensembles in the form of sandwich woven structure and 3D spacer knit structure are provided in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2: PEG developed by a sandwich woven structure

Figure 3: PEG developed by 3D spacer knit structure of textiles

Followed by PEG, TEG turns out to be the next promising source of energy harvesting as it targets capturing energy through most of the naturally occurring motions. The schematic representations of different methods of energy harvesting through triboelectricity in an ensemble are given in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4: Principle of triboelectric energy harvesting

Figure 5: Voluntary and involuntary motions in a human body leading to triboelectricity

Researchers at Georgia Institute of Technology have come up with a hybrid energy harvester based on triboelectric and photovoltaic principles, thus leading to generation of power through solar energy as well as through motion of the wearer from TENG-based ensemble. Another research at Georgia Tech reports development of energy harvesting yarns on the principle of triboelectricity. These yarns can be integrated with any common garment made up primarily of polyester, cotton silk and wool and these are washable as well. They are capable of harvesting energy while a dog walks or one waves his or her arms. The design is relatively simple, in the form of core shealth structure where core is made up of flexible steel fibre yarn of 50 micrometre diameter (acting as conductor) while the shealth could be of cotton/polyester (acting as dielectric material). Close proximity of these two materials having varying electronegativity enables the electrons to jump from the dielectric to the conductor. The stretched state of yarn leads the shealth part to come close to core part and go away when relaxed. Also current is generated when two layers of fabric, say sleeve with body rub against each other. These generators can harvest in the order of tens of milliwatts per square metre. Though it may not sound to be huge, but a triboelectric generator in the size of a jacket could make 100 mW of energy just from the wearer’s fidgeting which is enough to power small sensors or to send a burst of data a few hundred metres away. For testing, a small patch prepared by this yarn was sewn to the sole of a sock. It was found to charge a capacitor of 1V after 19 seconds of walking. This was found to be functional till 90 per cent humidity, hence proving its ability to work during heavy sweating. Further it sustained upto 120 cycles of washing machine.

| Presently, almost all the commercial products existing in smart wearable market rely on external power sources in the form of conventional batteries either for one time usage or rechargeable. As per a study conducted by Swedish Environmental Research Agency, each kilowatt hour of batteries produced generate an equivalent of 150 to 200 kilograms of CO2. |

Figure 6 is a schematic representation of development of a nylon yarn coated with silver, insulated with silicone and 4-plied to be knitted along with 3-ply twisted cotton yarn to form a triboelectric nanogenerator. This is an example to enable readers realise the beauty of textiles and the opportunity it provides to engineer a product by varying material and structure at multiple levels, in multiple forms, be it chemical or physical.

Figure 6: Yarn-based triboelectric generator

I know that by now you are flooded with a lot of examples of textile-based energy harvesters from the laboratories. A few I came across were of photovoltaic form, which do not fascinate me much as a student of Textile Engineering.

Dutch designer Pauline van Dongen collaborated with Christiaan Holland from the HAN University of Applied Sciences and solar energy expert Gert Jan Jongerden on the Wearable Solar project, which seeks to integrate photovoltaic technology into comfortable and stylish clothing. The two prototypes, crafted from wool and leather, feature segments with solar cells that can be revealed when exposed to sunlight or discreetly folded away, becoming virtually invisible when not in direct use. The coat incorporates 48 rigid solar cells, while the dress incorporates 72 flexible solar cells. If worn in full sunlight for an hour, each prototype can accumulate enough energy to charge a typical smartphone by 50 per cent. As fossil fuels deplete, it becomes imperative to explore sustainable alternatives and the Wearable Solar project taps into the abundant energy provided by the sun. In similar manner, brands like Tommy Hilfiger came up with jackets with solar panels made up of silicon and patched over the back panel of the jacket fastened by snap buttons and available on e-Bay for US $ 400.

Figure 7: Solar garments designed by Pauline van Dongen

In 2022, Pauline unveiled a vision to ‘reupholster our built environment’ using a solar-energy-generating textile (Figure 7) which she is developing with manufacturer Tentech. The fabric is named as Suntex. It is reported to be a durable and water-resistant solar textile that could be used to clad entire buildings, turning them into huge solar-energy generators. The fabric is developed by weaving organic photovoltaic (OPV) solar cells made from certain polymer, together with recycled yarns.

Well, if you try exploring the commercial market in this area, you will find it majorly dominated by photovoltaics. Though PEGs and TEGs are seemingly promising, they are yet to get popularised commercially. But the days are not far when the manufacturers of e-textile based smart garments would, if not by choice, be enforced by laws to integrate their products with such energy generators, in order to adopt sustainable approach. Not only this, a couple of years back, it was reported by Information Technology Laboratory that military forces go through more batteries than bullets on war front. Partly because a soldier has to dispose of 70 per cent batteries on field which they carry otherwise. In order to ensure that the battery does not fail in the field, at the beginning of the mission they change all batteries, which takes about 40 minutes. In present day era of modern arms and ammunitions, one cannot risk the operation owing to absence or failure of batteries and energy harvesters are one of the most suitable solutions as replacement. This fact yet again motivates the researchers and the industry to go ahead with such energy harvesting capabilities!