Apparel manufacturing is labour-intensive and requires a significant amount of repetitive work; the need now is to have skilled workers so as to do these operations faster (without frequent breaks), precisely and with high precision. Due to the repetitive and quick action, researches have shown that sewing machine operators have substantially higher risk of muscle pain and injury than workers in other jobs and the frequency of neck and shoulder injuries increases with years of employment. Ergonomics has not been given due attention as far as apparel manufacturing is concerned, especially in countries like India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. In this edition of the series on IE, Manoj Tiwari, Associate Professor, NIFT Jodhpur and Dr. Prabir Jana, Professor, NIFT Delhi discuss ergonomic aspects of apparel manufacturing, ergonomic work assessment and safety issues.

With the advancements of technology, competitive work environment has become more challenging, making the field of ergonomics more versatile and crucial for industries irrespective of the field. Ergonomics has a much wider definition in current context, which is concerned with improving the productivity, health, safety and comfort of people, promoting effective interaction among people and technology and the environment in which both must operate. The term ergonomics was coined from the Greek words ergon (meaning ‘work’) and nomos (meaning ‘rules’). The better the fit, the higher is the level of safety and worker efficiency.

Prima facie, apparel manufacturing seems a light work involving small sewing operations that too in sitting posture. But factors such as repetitive nature, precision, level of concentration and work postures during activity make it more complex and challenging on health parameters. Research conducted in trouser manufacturing has revealed that to sew one seam which is having standard time of 10-15 seconds per trouser leg, an operator needs to repeat the same action more than 1,500 times during the work day. This involves continuous movements of the same parts of the body maintaining a great amount of precision level each time. While measuring the force involved in these activities it may be noted that an operator lifts an average 406.10 kg of trousers per day and exerts an average total force of 2,858.40 kg with the upper limbs and 24, 267.90 kg with the lower limbs. Such kinds of repetitive work over the years results into muscular-skeletal Disorder (MSDs). In addition to this, recent studies have expressed concern about sewing machine operators’ exposure to high levels of electromagnetic fields (e.m.f) generated by sewing machine motors. These studies have indicated that there may be an association between increased levels of Alzheimer’s disease in such operators.

Working in a constant position for a prolonged period of time, such as sitting and working on machine for hours, working in standing postures, for example in cutting department or on embroidery machine, are examples of static posture. If the worker stands in one position for long periods of time, muscles of the back and legs may be constantly activated, which may lead to an increased fatigue and decreased blood circulation to the legs.

Some of the most commonly observed scenarios in apparel manufacturing are as below:

- Repeating the same motion throughout the workday.

- Working in awkward or stationary positions.

- Lifting heavy or awkward items.

- Using excessive force to perform tasks.

- Frequent lifting, carrying, and pushing or pulling loads without help from other workers or devices.

- Increasing specialization that requires the worker to perform only one function or movement for a long period of time or day after day.

- Working more than 8 hours a day.

- Working at a quicker pace of work, such as faster assembly line speeds.

Unfortunately, in the field of apparel manufacturing, especially in India and Bangladesh, ergonomics has not been given due attention yet. We are still working with improper work place designs resulting into poor productivity and quality as well as high labour turnover.

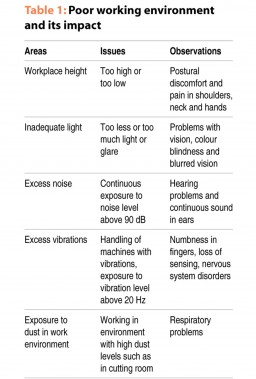

Workplace safety issues

As far as apparel manufacturing is concerned almost every area has potential of improvement on ergonomic aspects. Right from fabrics & trims stores to cutting to sewing, packing and finishing, ergonomic interventions can make a significant difference. We observe a significant mismatch between specific requirements and actual workplace arrangement. Table 1 shows some commonly observed examples of poor working environment and its impact in context of apparel manufacturing.

A watchful observation of how activities take place in a particular department may give valuable insights, provided IE has a basic understanding of ergonomics and its principles. One must observe the things from an operator’s point of view who is always on floor and involved in a number of physical tasks. The aim should be on minimizing the efforts (it may be physical or mental) while accomplishing the task. To achieve this (minimizing the efforts by an operator) an IE should work towards developing ergonomic solutions and providing necessary training. Table 2 gives some insights on department-specific work place safety issues related to ergonomics and recommendations.

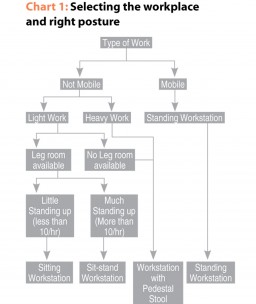

Selecting the workplace and posture

Most of the work in offices as well as in manufacturing setups (such as garment stitching, assembly work and packaging work, etc.) is done in sitting posture. Generally, working in sitting posture is preferred over working in standing posture as it has a number of advantages compared to standing. The body is in better comfort because of the available support from floor, seat, backrest, arm-rest and work surface. Type of work and level of mobility required, play a critical role in deciding on the right working posture. Chart 1 may be referred for the selection of right posture and accordingly workplace may be developed or arranged.

Adjusting the right posture

Posture is often decided by the task or the workplace where or on which the task needs to be performed. Maintaining the right posture while working is very important and to do, this it’s imperative to work on analyzing the task critically. The arrangement of workplace and/ or the workstation should fit to the operator so that the right posture can be maintained. A logical approach for posture selection is shown in Chart 2.

Ergonomic vulnerability assessment

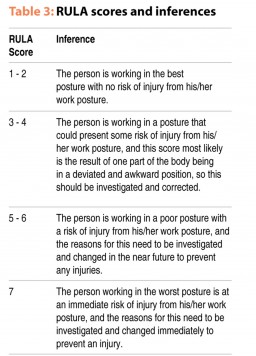

There are a number of assessment techniques used by ergonomists for postural analysis and to check the vulnerability. Some of these techniques are RULA (Rapid Upper Limb Assessment), REBA (Rapid Entire Body Assessment) and OWAS (Ovako Working Posture Analysis System).

RULA – Rapid Upper Limb Assessment (RULA) is a survey method developed to measure exposure of individual workers to risk factors associated with work-related upper limb disorders. RULA provides an easily calculated rating (From Level 1 to Level 4) of musculoskeletal loads in tasks where people have a risk of neck and upper-limb loading. The tool provides a single score as a ‘snapshot’ of the task, which is the rating of the posture, force, and movement required. These scores are grouped into four action levels that provide an indication of the time-frame in which it is reasonable to expect risk control to be initiated. The RULA scores (as mentioned in Table 3), highlight the urgency about the need to change how a person is working as a function of the degree of injury risk.

How to do vulnerability assessment

Such analysis is recommended to be done by trained professionals. Precision in body posture measurement is key to any such analysis that can be done by taking snapshots using photography or videography. Calculation of scores and levels can be done manually using standard formats, where a particular value is assigned to a particular posture depending on the bend/angle of body parts while doing the work. (Please refer Figure 1 for step-by-step RULA procedure). The body parts considered for assessment are: 1. Arms & Wrists; and 2. Neck, Trunk & Leg (just to check for support to leg while working). A higher score and level indicates an increased vulnerability and highlights the need of posture improvement. The same may be achieved by either developing improved method, improved equipment and/or by correcting the posture while working.

REBA – The REBA (Rapid Entire Body Assessment) technique is a postural analyses system for musculoskeletal risks while working in different postures. While RULA is applicable only to upper part of the body, REBA system includes entire body, such as the upper arms, lower arms, wrists, trunk, neck, and legs. The method reflects the extent of external load/ forces exerted, muscle activity caused by static, dynamic, rapid changing or unstable postures, and the coupling effect.

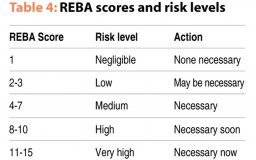

There are five REBA scores and risk levels for evaluating the level of corrective actions as mentioned in Table 4.

How to do vulnerability assessment

REBA technique is used for entire body postures as it covers leg movements also. For analyses, photographs or video of posture while working may be taken. Specific values (refer Figure 2) are assigned during – 1. Neck, Trunk and leg analyses; and 2. Arm and Wrist analyses. A number of factors, such as twist, load, level of gripping/ handle and activity (range and frequency) are also considered in calculating the final REBA score. Like RULA scores and levels, in REBA also a higher score and level indicates an increased vulnerability, and highlights the need of posture improvement.

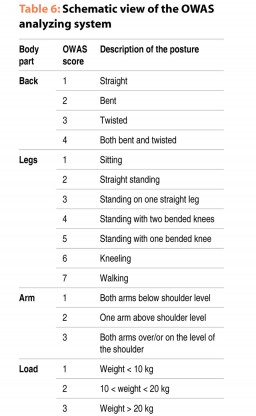

OWAS – OWAS (Ovako Working Posture Analyzing System) method was developed in mid1970s and is one of the simpler observation methods for postural analysis. The OWAS method has proved to function well in practice and it has been fruitful in achieving improvements in the work system and in preventing health problems. The OWAS method is easily adaptable to daily workplace analysis and is capable of evaluating numerous postures at a variety of workplaces.

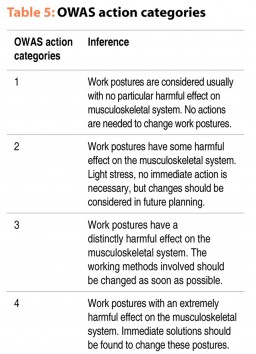

The OWAS method can be used to standardize ergonomic evaluation of the postural load and improvements and planning of workplaces, work methods, tools and machines. When using the OWAS method in job analysis the job is usually divided into tasks. By analyzing the working postures at all the tasks, the whole posture analysis of a job is carried out based on the OWAS action categories mentioned in Table 5. Schematic view of the OWAS analyzing system has been shown in Table 6.

Conclusion

In apparel manufacturing, ergonomics is a neglected area and has not been given due attention. The key issue is that most of the IEs consider ergonomics as an allied field with no or little correlations with work study. On the other side, the top management and owners seem to take ergonomics as something which involves a significant amount of investment with no returns. This thinking makes them not very concerned with basic ergonomic issues at workplace. The reasons of not applying ergonomics up to a great extent by IE may be the lack of understanding of ergonomic principles or a colonial mindset of IE of not providing comfortable work place to operators. It has been practically observed that small ergonomic interventions with minimal investment create a significant difference in productivity and efficiency of an operator. While putting efforts on method improvements and time study, an IE should also observe the ergonomics involved and consider it equal or even more important. Garment manufacturing involves a number of repeated actions which an operator does throughout the day and same is continued as regular on every day. Such repeated and monotonous task may lead to discomfort to the worker and eventually may result into body disorders. As a common remedy, job rotation is widely recommended to bring variation into repetitive and monotonous muscular work. However this in itself is not sufficient as in job rotation also the time and load may remain more or less same. It requires a complete work process re-engineering, where an operator is spending lesser time in monotonous and repeated task and the whole body is used in a dynamic manner.

A sincere and honest effort (involving ergonomics) towards making the workplace safe and comfortable may bring positive vibrations and a new inspiration towards work and eventually translate into an increased job satisfaction and improved labour retention.

Case Study: Vulnerability assessment using RULA, REBA and OWAS

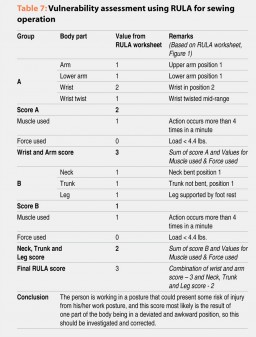

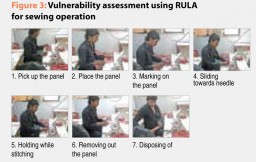

Let’s try to understand vulnerability assessment using RULA where an operator does a sewing work. This involves a numbers of steps (refer Figure 3) such as pick up, place the part on machine table, marking, slide towards needle, stitching, removing out after stitching and finally disposing of.

Now using table for RULA employee assessment worksheet as shown in Figure 1, RULA needs to be performed for each posture for the given operation. Let’s do analysis for activity of picking up the piece (refer Picture 1 of Figure 3). Table 6 shows different components and respective values (with justification) based on RULA technique.

In similar fashion, vulnerability assessment using REBA may also be practiced. Now let’s do vulnerability assessment using OWAS for the same posture. Please refer Table 6 for OWAS analysis of same operation (pick up the panel) as per Picture 1 of Figure 3.

It may be noted that the vulnerability assessment done using RULA and OWAS is only for one posture (that is pick up the panel) as per Picture 1 of Figure 3. Such assessment is recommended to be done for all the postures of the operation also. Based on the score (from RULA/REBA/ OWAS) for each posture inferences should be drawn and corrective actions taken.