Much effort is expended in garment factories in moving work from machine to machine and department to department. This is an additional exercise for which the customer does not pay! How the work moves through the factory is, of course, to a large degree dictated by the building in which it is housed. In this second series of the article, Paul Collyer discusses movement between different departments or different cost centres and their implications.

The different production-related departments commonly identified in factories are raw material store, spreading and cutting, sewing, finishing & packing, finished goods store, etc., while the non-production departments include administration, design, merchandising, etc. The existence of additional departments like CAD, embroidery, washing, etc. depends on the type of merchandise and whether all operations are being carried out in-house or being outsourced.

Movement of goods between any two departments is also influenced by factors such as whether the movements are two directional or unidirectional. An example is movement of cut panels between cutting and embroidery department. Selected cut panels are sent to embroidery section and after embroidery, the embroidered parts come back to cutting section for bundling and distribution or are sent to sewing department for sewing. If former is the case, i.e. embroidered parts come back to the cutting section for bundling and distribution, then additional transport is being performed and in that case, processes should be reviewed and the status quo challenged.

The ideal intra floor material movement should, in conventional line of production, preferably take a route either along the length of a factory or double back in a U-shape to avoid unnecessary transport of completed or part completed garments.

Wherever possible, departments should be laid out in a way that that criss-crossing of both people and goods is minimized. Although, it has to be recognized that in the real world, some disruption is inevitable.

The overall objective is to minimize the distance of flow path; this can be easily measured manually using string diagrams. Even within a department location of machine and/or operation can be optimized by analysing string diagram method.

When producing most garments, it is preferable to start to transport work on trolleys either in bundles or in “block” and the layouts shown make deployment of trolleys simple. When complex garments such as gents’ jackets are produced, then it is feasible and indeed advantageous to work with subassemblies, all on trolleys and then collate to an assembly section using overhead transporting systems.

Again it is a simple task to lay out the factory floor for any mode of garment transport in a single storey unit unencumbered by support walls and pillars for other levels.

The following two examples concentrate on demonstrating how the floor layout affects both the flow of goods and can assist the implementation of company labour policies.

Case study 1: Sanghar Overseas

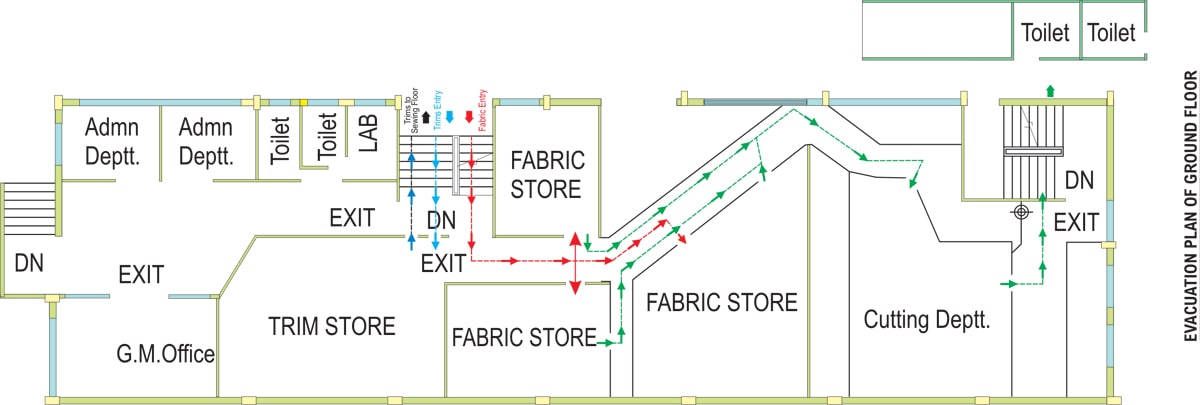

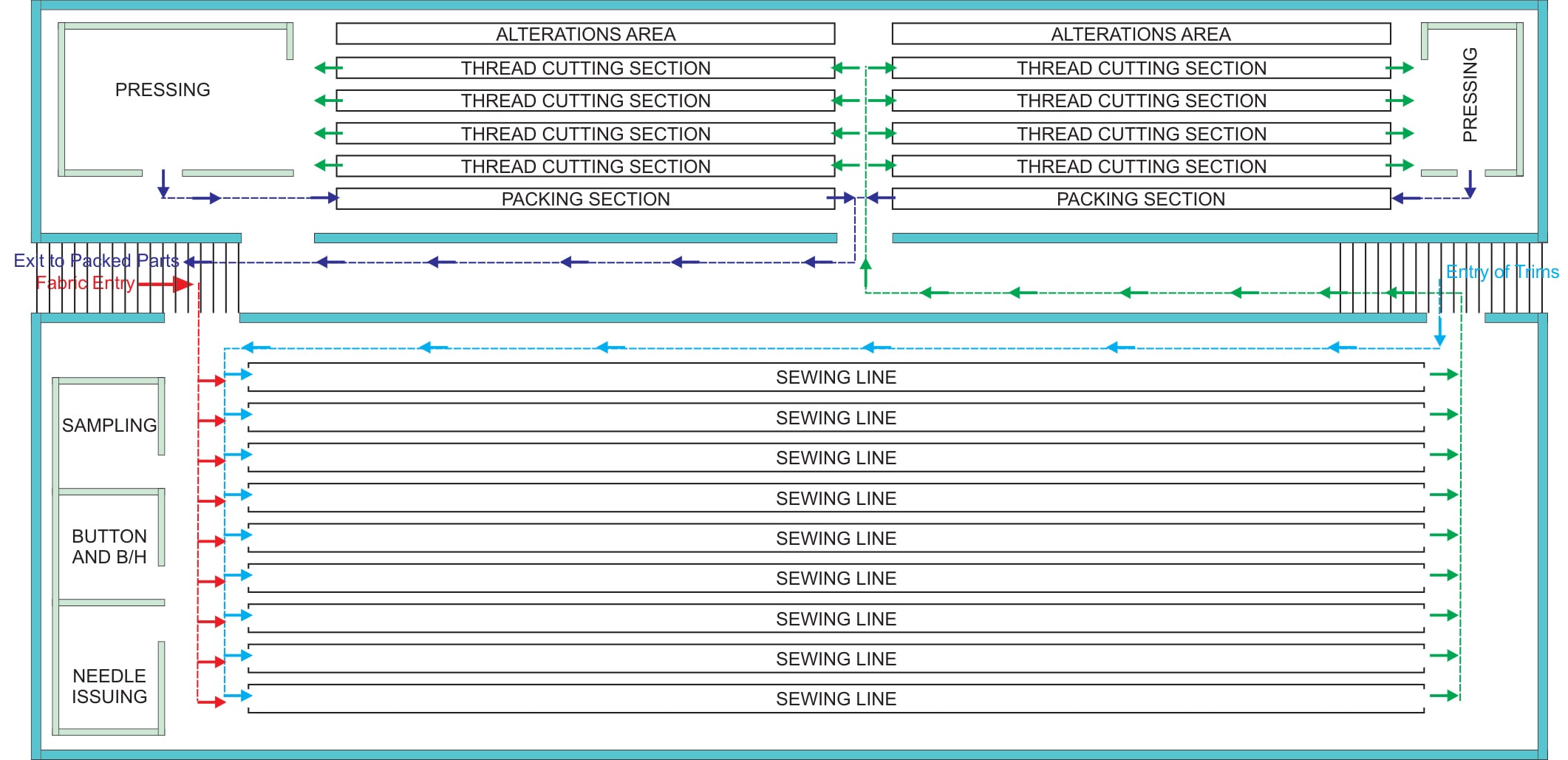

In Figure 1.1, ground floor layout, both fabric and trim store are located adjacent to cutting department enabling bundling of cut parts with required accessories before dispatching to sewing department. Additionally the cutting department location close to staircase optimizes cut parts movements to the sewing floor downstairs.

In the plan shown in Figure 1.1, having the cutting department closer to factory exit also helps (less distance covered) sending cut parts for embroidery or sewing subcontractors. Additionally locating the cutting department on the ground floor requires extra movement of work down to the basement for sewing and then up for finishing. However, as previously stated it makes the movement of goods to and from subcontractors easier. This is an example of the “trade off” which the managers must consider when deciding on factory layouts.

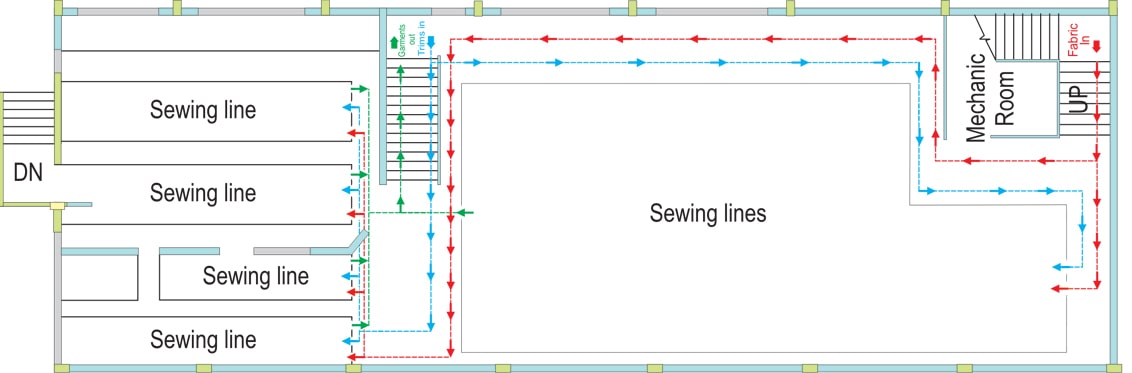

The sewing section at basement as seen in Figure 1.2, does not have bundle distribution section, which means bundles are made in cutting section and transported to sewing section. However, a bundle distribution closer to sewing section would have added flexibility.

Mechanic room at sewing floor would again optimize mechanic’s travel and quicker attending to sewing machine problems.

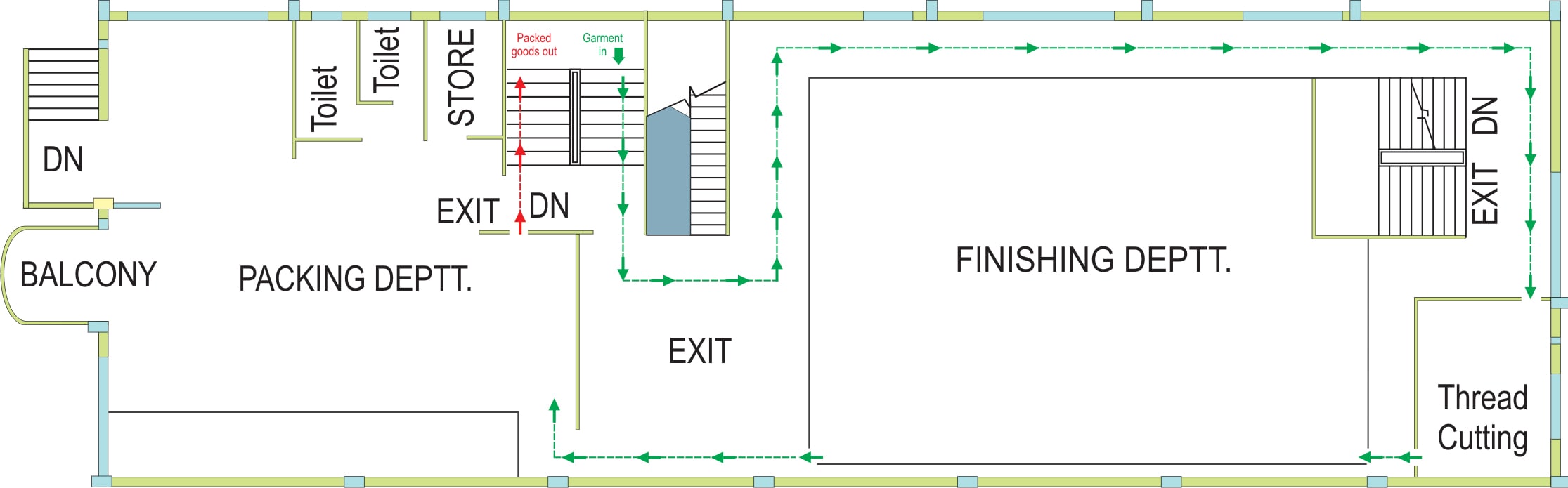

Finishing and packing department at second floor Figure 1.3, requires finished garment from basement to travel all the way up.

If we take a look at the basement, we find that the entry and exit points of material are reasonably good. There are no extra movements. But when goods are received on the 1st floor, they have to travel a lot to reach the thread trimming section. As thread trimming is the first operation after garments come from sewing, it should have been located closer to centre staircase.

However, if the side staircase is being used for movement of goods then the existing layout makes a perfect sense as the goods move from thread trimming to finishing to packaging section sequentially. However, this is not even the right solution because if the goods travel through the side stairs then they have to exit the basement floor (sewing floor) through the side stairs, which means extra movement for the goods in the basement to make an exit. As already stated an optimum solution would be to have the thread trimming section near the central staircase, this would not eliminate entirely the extra movement as the goods still will have to take a U-turn to reach the packaging section, but at least this extra movement will be reduced.

Case Study 2: Orient Craft

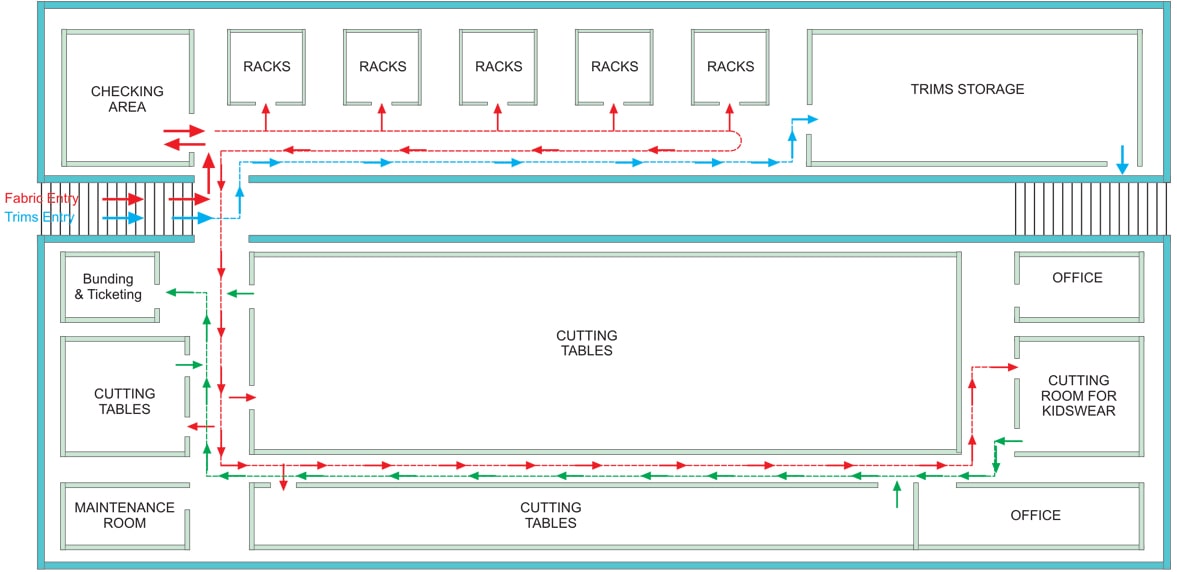

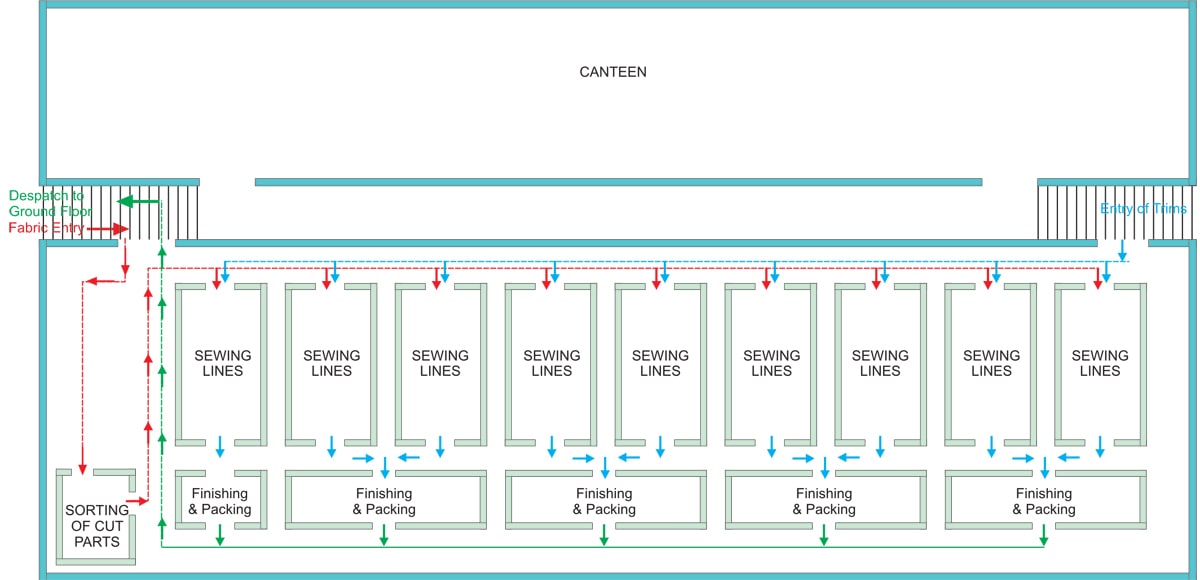

Basement is having fabric and accessories storage and fabric cutting. Two staircases at opposite direction as seen in Figure 2.1, enable unidirectional flow of goods. While both fabric and accessories enter from left staircase, trims are being issued to sewing department from right staircase. Bundling and ticketing section is currently located at left corner, assuming trims are being issued separate from cut parts, component bundles will move to upper floor through left staircase while trims will use right staircase.

Probably relocating bundling and ticketing section closer to right staircase would have reduced distance of travel by goods. It would also mean that the cut parts along with trims will enter together from left staircase and leave together from the right one. This would reduce the probable criss-crossing at the left staircase.

In Figure 2.2, we see that the 1st floor has 9 sewing lines in one side and canteen on the other. Having canteen on 1st floor is unusual as generally canteen is located at top floor. Sewing maintenance room ideally should be located closer to sewing lines. Here maintenance room is located at basement, resulting in movement of faulty swing machine all the way from 2nd, 3rd, and 4th floor to basement for any major repair.

Sorting out of cut parts and bundle distribution is done closer to sewing line on 1st floor. While this results in lesser movement of goods for sewing lines located on the 1st floor, bundles need to travel up to 4th floor from first floor distribution area. Having bundle sorting area closer to left staircase optimizes bundle movement to all floors.

Left staircase is being used for movement of cut parts upwards and movement of finished goods downwards, in Figure 2.3. As right staircase is being used for movement of trims upwards, sections like button attaching and buttonholing and needle issuing should have been located at right corner of every floors. Currently these are located at the left corner, resulting in unnecessary movement of trims from right to left at every floor. One interesting point of Orient Craft layout is the decentralization of responsibilities. Every sewing floor has separate check/finish/iron/pack section. This type of layout gives flexibility in operation as well as separate floor incharge can be made accountable.

The following examples of bra and jeans production explain how layouts influence the way managers and supervisors are able to organize the work flow and operators in a manner that permits effective use of labour and equipment.

Case Study 3: Bra production

A product with a vast array of styling features but even so with common operations. At the beginning, joining of cup shells with a 3 step zigzag machine is very short cycle and can be done in a small section. More importantly the operations at the end lend themselves to a specialist section, for e.g. operations regarding front cradle and wings and all wire insert and bar tacking and bow attach. This situation affects factory layout thinking in that it is possible to equip all production lines with operators and machines to complete all operations.

However, most of the operations mentioned are very short cycle and operators become very expert. Balancing such a line to maintain high operator performance and utilization is difficult for all but the largest section. It is far better to have a number of smaller assembly sections that feed part completed garments to a common finishing section. Where will this section be situated? Will it be at one end of a sewing floor or in the centre so that all lines supply it? The answer is of course dependent upon the dimensions of the sewing floor and a second major consideration.

Bras and most other lingerie do not need pressing. It is therefore possible to pack immediately after garments leave the production line. Many companies place packing on a separate floor from sewing. However, production balancing not only concerns sewing operations on the line it is also about the flow between departments or functions. Good practice is to make a floor manager responsible for all operations, he has to balance flow and has not hit targets until garments are made and packed ready for packing in the correct ratios. This approach focuses the manager’s mind on ensuring a correct, steady flow of garments to packing and not dumping in a disorganized manner to suit his sewing output.

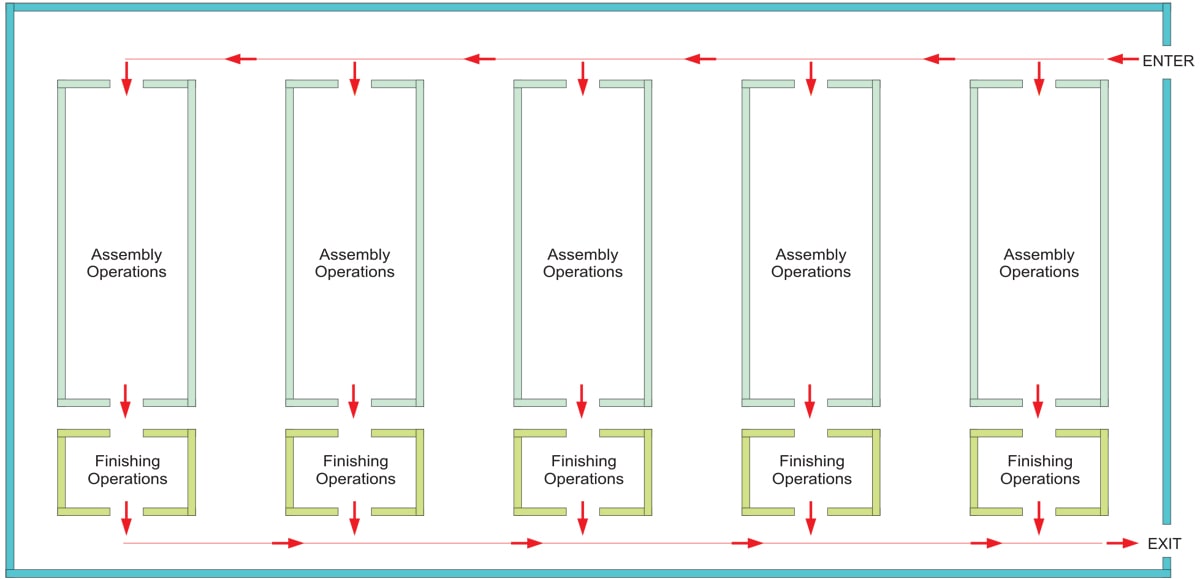

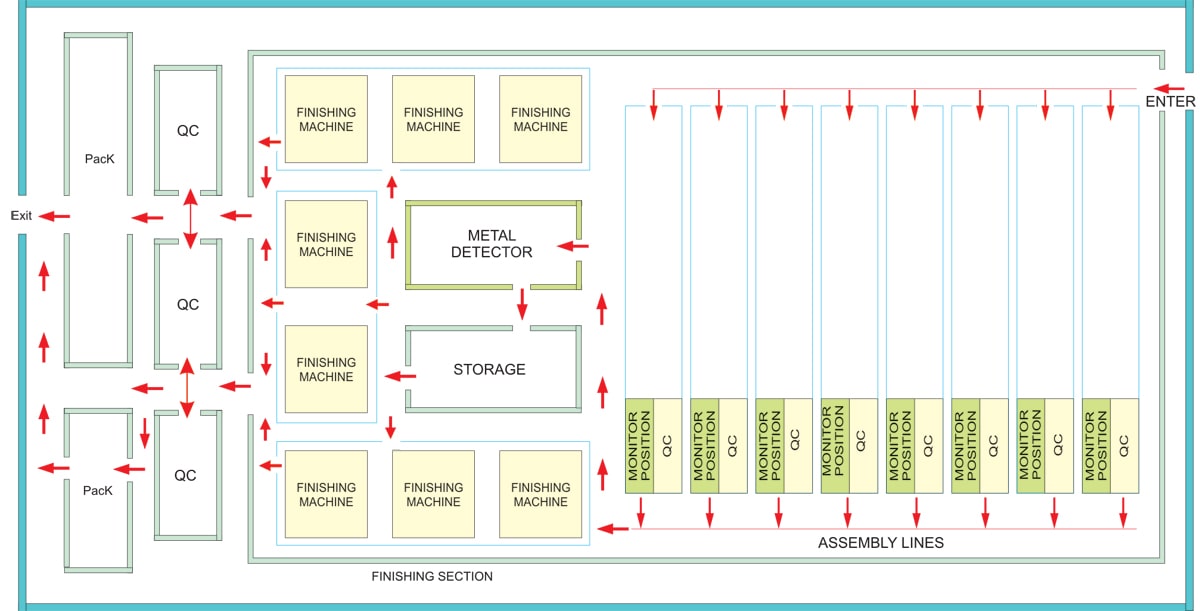

In option 1 (Figure 3), the traditional approach has been taken and all sewing operations are completed in the line. Packing is done in a separate department. This has the advantage of making a supervisor responsible for all the garment but fails in that most finishing operations are very short cycle and the line is unlikely to be able to keep operators fully occupied on even one or two jobs. Balancing therefore becomes difficult with detrimental effects on both efficiency and operator performance.

It should be remembered that finishing operations on bras such as bow attach, hook and eye and bar tacking are common to most styles.

In option 2 (Figure 3), the traditional line has been retained but the finishing operators move between lines, roughly two sets of operators between three lines. This “half way” approach improves operator performance but requires supervisors to cooperate or for specialist supervisors to control the finishing operators.

In option 3 (Figure 3), the common finishing operations have been removed from the line into specialist sections that are equipped with all necessary machines. Dependent upon thread colours etc., sets of machines will be allocated to styles but operators will be expected to move from style to style still performing the same operation. Sewn garments pass through QC and are then packed on the sewing floor. This more innovative approach means that finishing operators are allowed to specialize maximizing their performances. Additionally finishing and packing staff can be easily prioritized onto urgent deliveries. Managers are also encouraged to monitor and match production to packing ratio requirements as their output targets are based on packed garments.

Case Study 4: Jeans production layout

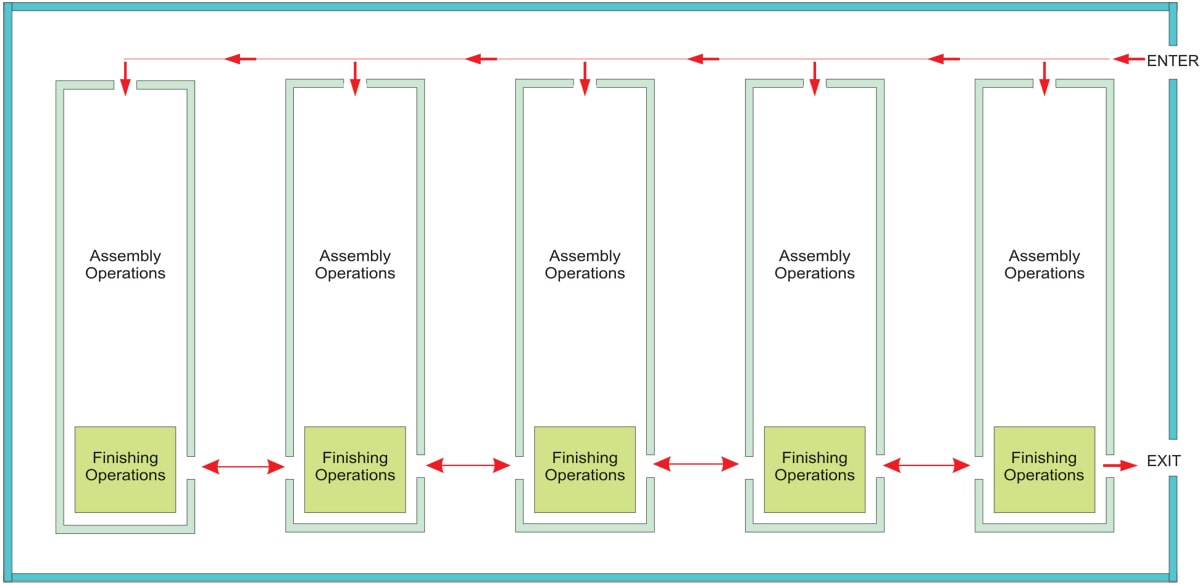

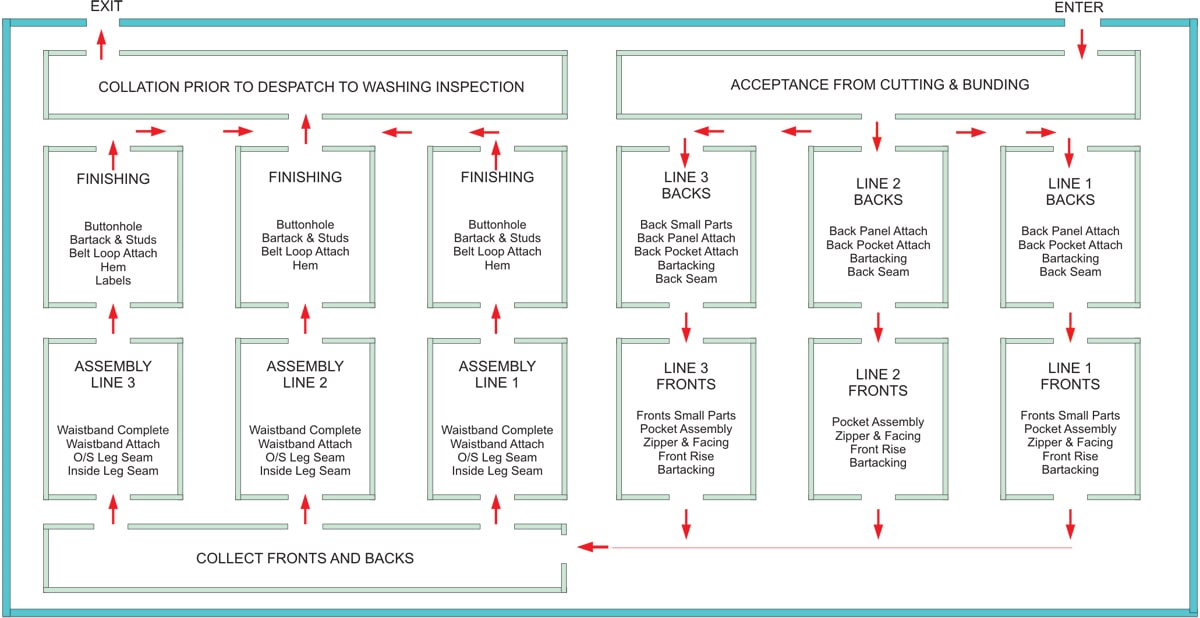

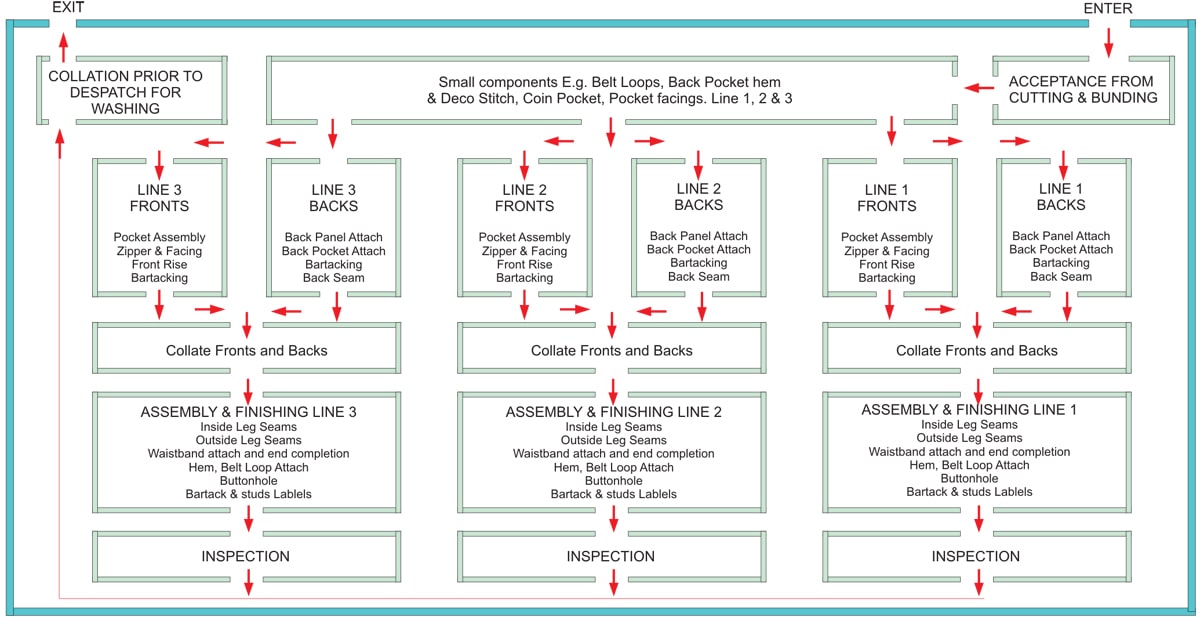

There are many operations that are performed on small components and are of short cycle at the beginning of production e.g. hem coin pocket, attach coin pocket to facing, make loops, hem back pocket, deco stitch back pocket. These can all be done in “block” in a preparation area and then collated into bundles.

Additionally it is standard practice to have teams within a line making fronts or backs. In a multi storey unit how many lines can be accommodated on one floor and do they have sufficient capacity to need their own front and back teams or is it preferable to have both common and back teams that supply several assembly lines? Alternatively are backs made on one floor, fronts on another and then transferred to specialist assembly floors. In jean production the manager then has to consider whether to equip every floor with finishing facilities such as loop, button and label attach, bar tacking and buttonholing; all short cycle or does he have a specialist unit servicing all lines output, possibly on a separate floor.

Whereas all factories have to make these choices the manager with a single storey unit has freedom of choice whereas his counterpart in a multi-storey unit may have decisions forced upon him by the layout and size of floors and the transporting between storeys.

In option 1 (Figure 4), small common operations are performed in a “small parts section” that feeds all lines. Each line has its own front, back, assembly & finishing (button, buttonhole, belt loop etc) sections. Advantage is that each line manager is responsible for the style and output. Disadvantages are that lines are dependent upon the small parts section performing and providing them all with the required amount of work, and production balancing problems as many operators will have to do two jobs to keep busy in addition they are susceptible to absenteeism. Furthermore the lines will need to be large to provide finishing operations with sufficient work leading to poor utilisation of both operators and equipment.

In option 2 (Figure 4), specialist front and back sections, incorporating operations previously done in a small parts area produce for all lines and styles. The sub-assemblies arrive at the end of the sewing floor and then move down assembly lines, each dealing with an individual style to a specialist finishing section.

Considering layout both options are adequate but the first has the disadvantage of finishing garments which then have to be transported the entire length of the floor to an exit point.