Due to various pressures on the manufacturers to improve productivity, it has now become even more important to make fuller use of existing facilities and to utilise low cost improvements to make the production process more effective.

One common misconception is that workplace engineering is only for larger companies to increase productivity. This article is intended to include the smaller manufacturer with limited resources who by utilising the basic principles of movement and a little imagination will be able to make significant reductions in garment work content at minimal cost.

Effective handling of garments by the operator depends upon both the facilities made available in the work station and the skill of the operator. Skill should be instilled into the operator by suitable systematic training in which the most efficient method of handling is explained and practiced over and over again until it becomes automatic. This can only be accomplished if all the required components are presented in a systematic manner. When the operator has to search for a component, the automatic rhythm of his work is broken. This requirement is one of the key factors in designing a workstation layout.

If we accept that 80% of the operator’s time is spent handling garments and components during loading on to the machine, sewing, guiding under the needle and disposing then, as previously stated, it is essential to optimise the workstation so as to maximise output and reduce costs by ensuring automatic repetition of handling methods.

By analysing an individual operation the manufacturer can adapt a workstation using very cheap materials. The key principles are:

- The component must be stored as close to the needle point as possible ensuring that it does not interfere with the sewing operation.

- It should be stored in a position so that it can be presented to the needlepoint ready to travel in the direction required i.e. it does not need to be turned through 90 degrees or more.

- Where more than one component are worked then wherever possible the operator should be able to pick them up simultaneously.

- Wherever possible the operator should be able to grasp and release a component by only moving his arm from the elbow joint or failing that by engaging his whole arm from the shoulder and not having to move his upper body.

- Components should be stored in or as near to the same plane as the machine table.

- In practice, however, whatever the operation, many operators tend to store components:

- On their knees – usually because they do not have the facility to keep them anywhere else or through habit. It is therefore necessary to lift the work to the level of the machine bench. As fabric is not rigid, when a piece is lifted it goes ‘out of control’ and requires extra handling to position it again.

- On tables, or upturned boxes, to the right of the machine. It is not possible to load components to the machine foot from the right. Therefore the operator has to bring work the entire length of the machine, transfer it to the left hand and re-grasp it before presenting it to the needlepoint.

Simple points but crucial in minimising handling and reducing time and relatively easy to correct!

Examples of how to use low cost improvements from men’s jacket production are shown below:

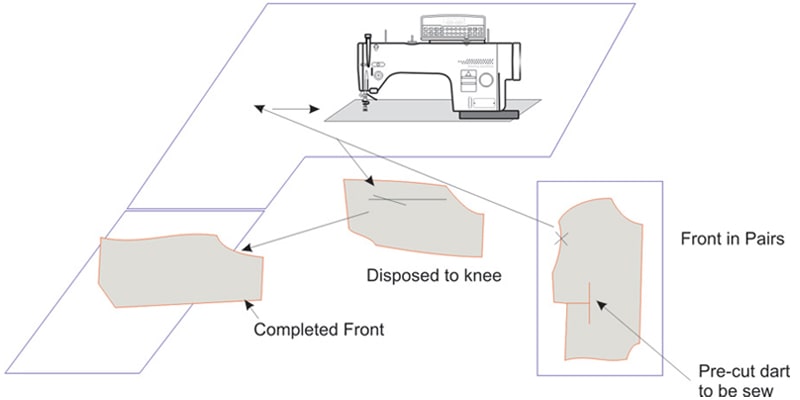

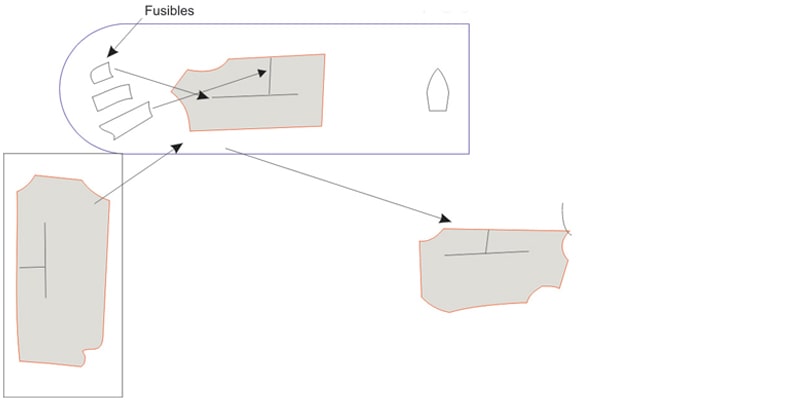

Fig1. Sew dart/front seam in jacket front. Original layout.

Pick up with right hand at point indicated X. Note that it is grasped on the edge but not at the point to be placed under the machine foot thereby necessitating a reposition and regrasp

In this operation the fronts (in pairs) are on a table to the operator’s right. The movement sequence includes:

- move the panel across the body, turning to right side.

- reposition on bench.

- align dart edges.

- move to machine foot.

- back tack and sew dart in one burst of sewing, auto cut threads.

- dispose by sliding onto knees.

- move 8 -10 fronts to storage on left.

The layout breaks the ‘rules’ as panels have to be moved across the body and a up a different level panel. Additionally the panel has to be moved through 90 degrees twice as it cannot be moved across the body in any other manner.

The true test is however the ‘stopwatch’. The operation was split into two elements or sections: dispose/load and sew. Using the original layout, times were for each side (in centi-minutes)

| Dispose/load | 0.046 | 48.40% |

| Sew | 0.049 | 51.60% |

| Total (cycle) | 0.095 |

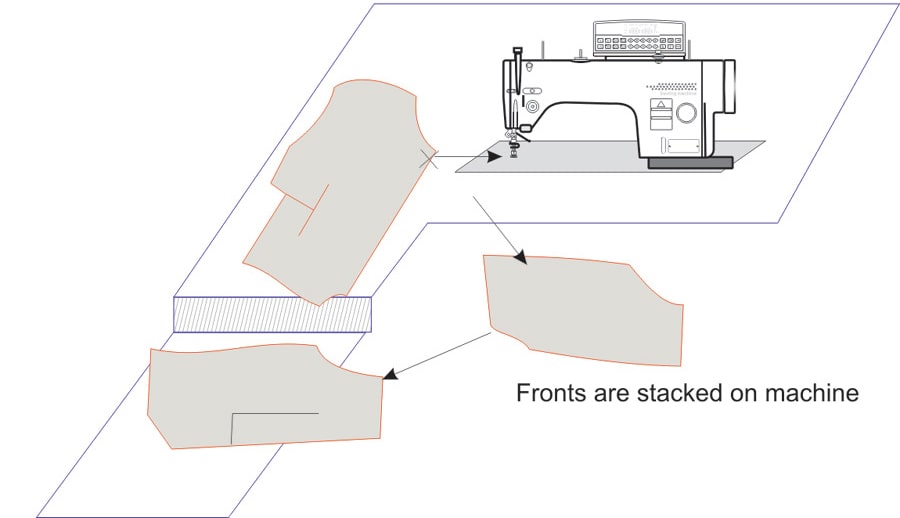

When the workstation was changed to fig 2 the operators initially slowed down as they were unaccustomed to the new movements and did not work automatically. However after practice they were able to reduce dispose/load to 0.027 – a reduction of 41.3% and 20% on the overall cycle time.

Fig 2. In this layout the operator collects from the machine table to the left (with extension) and can therefore work in the same plane, works on the garment and then disposes to his knees as before. Usually work would be stacked nearer to the machine foot but in this instance, as the fronts are laid in pairs, it is necessary to give sufficient space for every other one to be turned through 180 degrees.

The only additional cost in this case is a small melamine extension to the table.

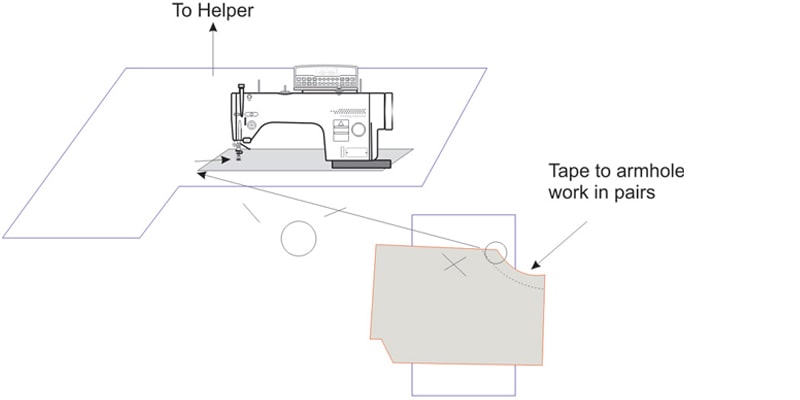

- Attach tape to front armhole

In this operation tape is applied by a single needle lockstitch machine to the front armhole. Again the fronts are stored in pairs on a table to the operator’s right. However disposal is by pushing forward away from the needle where a “helper” cuts and stacks. It should of course be noted that the use of a “helper” removes work from the sewing operator but doubles the standard minute content of the job. There are four approaches to the dispose:

- A high-tech solution is to fit the machine with an “impact” tape cutter and automatic stacker.

- A compromise is to fit an impact cutter and the operator disposes manually.

- The operator manually cuts the tape and disposes.

- Leave the helper in place.

There is of course no right or wrong answer – only cost/benefit analysis. What are the costs, what values are to be put through and therefore what is the payback time?

However if we forget the dispose, there is scope for improving the sewing operator’s output.

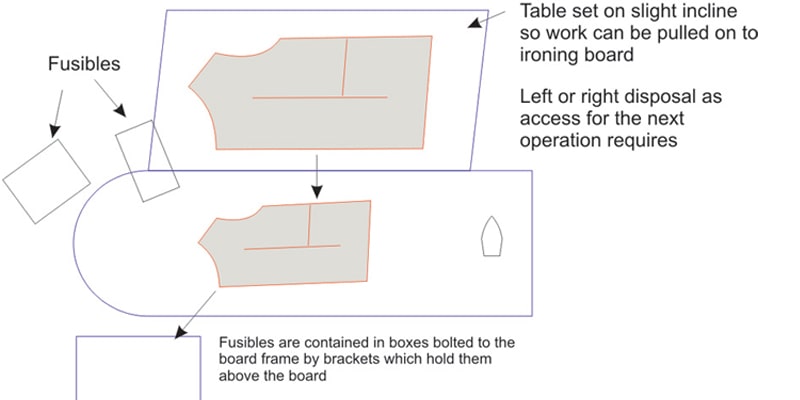

Fig 3 Original Layout

Time for load = 0.063 centi minutes per front (25.1%)

Time for sew = 0.188 centi minutes per front (74.9%)

Cycle time = 0.251 centi minutes per front

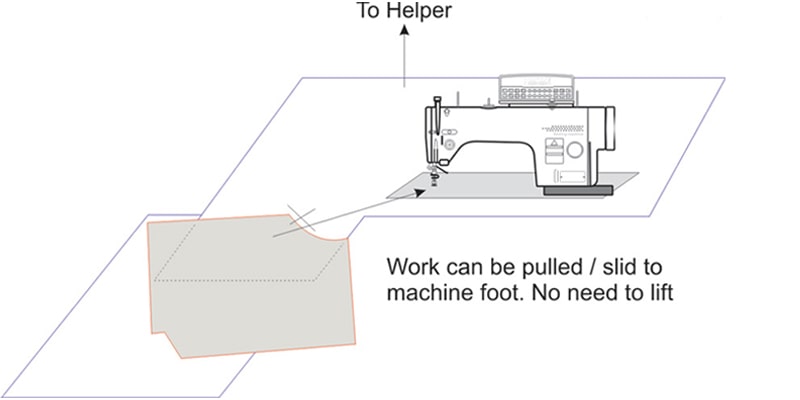

Fig 4 In this instance the sewing element is a much higher percentage of the total but altering the layout by extending the machine table to that shown in fig 4 reduced load time by 0.017 to 0.046 creating an overall reduction in work content of 8% with little effort and expenditure.

A reduction of 8% may not appear worthwhile but calculated at an SMV for two jacket fronts of 0.63 for the operation for the original method an operator performing at an 85% efficiency for an 8 hour day will produce 648 pieces. An 8% increase for minimum outlay gives an extra 52 jackets per day!

Iron front dart

Work station engineering does not apply to sewing alone. All operations can benefit.

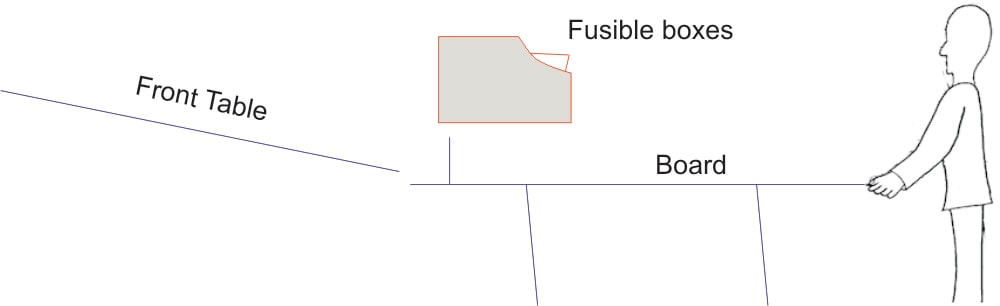

In this ironing operation the front dart is opened and fusible applied the top of the dart and the pocket opening to seal into position.

Original work station layout

Fig 5 and 6 In this example the operator has positioned the work to the left and disposes to the right, a more natural movement. However work has to be lifted, repositioned through 90 degrees and moved to the board and the cut fusibles are stored on the end of the ironing board and are prone to being knocked onto the floor (Fig 7).

| Timings | |

| Dispose/load | 0.10 centi minutes per front (36%) |

| Iron/attach fusibles | 0.26 centi minutes per front (64%) |

| Total cycle | 0.36 |

| New layout timings | |

| Dispose/load | 0.04 centi minutes per front (13.3%) |

| Iron/attach fusibles | 0.26 centi minutes per front (86.7%) |

| Total cycle | 0.30 |

A total reduction of 0.06 or 16.7%.

In addition to the time savings all operators will benefit from reduced fatigue. This is particularly relevant for the ironer who is standing, working with heat and lifting all day.

However it must be remembered that on its own, method and workstation improvements will have a marginal effect. They should be a component in a complete production management improvement programme including balancing, training and effective supervision. There is, after all no point in increasing the capacity of an operation by method improvement if the work supply is not adjusted. Also the operator is not a machine but a human being with his own interests uppermost and will need to be ‘sold’ the new method by effective supervision and management. Experience shows that when an operator realises a method improvement makes his life easier then he will be quick to grasp it. He may not however be so fast to embrace the concept of having to produce more garments or having his SMV reduced to reflect the new method!

It has already been stated that a different approach has to be employed when the jacket shoulders are joined and the garment becomes bulky to handle. This is where the benefits of the hanging chain system appear. However, for those companies transporting their work in small quantities by hand to each operation there are other saving options. If the principles of workplace layout and movements are observed, it is possible to improve most operations. Even the provision of a small table or machine extension so that a part assembled jacket can be stored near to the needle point, in the same plane as the machine bench and laid in the right direction can make an impact.