All apparel entrepreneurs share a common characteristic, that is of maximising production through the efficient use of the three M’s – Manpower, Machinery and Material. The humdrum of daily routine seems to lull the manager into accepting the existing practices without challenging them and seeking answers to questions like, “Why are we doing that and is it necessary?” and “Is there a better method to do it?” The menswear manufacturers have generally been considered to be the most traditional in the apparel industry. Paul Collyer seeks to change this conventional mindset by highlighting some of the problems commonly faced by the jacketwear manufacturers and by providing practical solutions on how to make the best use of the factory and workplace layouts. He urges managers to review the existing practices, so as to get the best out of the system.

In the garment factory, it is very easy for the manager to get sucked into the routine pace and day-to-day running of the unit. Adequate time is not being given to consider what is happening or how it is being done and the focus is on the result. Accordingly, many poor practices continue to be in use as no one has the time or, even worse, inclination to sit, think and challenge them. Procedures that served well in a small factory, continue to be followed even in an enlarged unit; new technologies are either ignored or not used to their maximum potential, as instead, they are adapted to fit the outdated practices of the factory. These conditions are particularly true in the handling and transport of garments and their components throughout the production process.

The layouts of factories, production sections, individual workstations and the deployment of associated garment handling and control systems are fundamental to the efficient running of a production unit. Each area of the factory has its own requirements but production practices should all be ultimately decided by a combination of need to ensure ease of workflow, garment handling, and effective utilisation of people and equipment, and not by adherence to traditional thinking and practices.

The operators are the key but they work within a limited ‘bubble’ of responsibility. It is the role of the manager to ensure that they have the requisite facilities to work most efficiently and thereby achieve the specified standards. These facilities include their ambient environment, i.e. the workplace.

If we wish to look at potential factory, section and workplace layouts and therefore the production system, operator performance and method of work, we must first consider what a sewing operator does all day. The sewing (or press or bench) operator is asked to perform repetitive tasks in a rapid and accurate manner. They have to be able to work speedily at a fast rhythm. The rhythm can only be maintained when a repetitive task can be continually repeated without interruption, (not do once, wait, do again, wait!). The operator’s movements should be the minimum possible, symmetrical, continual, natural and automatic. The method of work should allow them to perform in this way. The operator should not have to search for a component; the layout should have an ergonomic design so that they know where an item is, to facilitate easy pick up without any break in rhythm.

To summarise, the objectives are to enable the operator do his work in as effective a manner as possible by picking up his items automatically and effortlessly, while simultaneously maintaining a rhythm of work without any unnecessary actions. Having ‘set the scene’, we should now consider how the factory, section and individual workplace layouts impact on the working of an operator and hence on the production unit as a whole.

Current line layout

Undoubtedly, some of the most visible displays of a traditional approach to manufacturing can be seen in menswear factory layout in which production lines proudly display titles such as fronts, backs, linings, sleeves, and assembly where racks of components wait to be collated into garments. In this commonly seen system, garments are broken down into their components or sub-assemblies as described by the section-names prior to issuing them to the production lines and each is worked on independently for as long as possible. Garments are also usually heaped into small bundles until they are too large to be handled other than as individuals; this system is commonly known as Progressive Bundle System.

In this system, the factory layout often has a separate cutting room with fusing presses and a sorting and bundling area, parts preparation sections, where each produces a single component such as sleeves, collars, etc., a collation area to collate and match parts, an assembly area for final assembling of garment and a finishing and final pressing room.

Often separate component sub-assemblies progress down a line in small bundles and stored in a holding area before they are collated as and when required. In some instances, after shoulders are joined, individual garments travel on hangers, possibly on a basic rail system, although in many factories operators throw them to one another! Only when they reach final press, is an overhead rail transport facility used. This traditional approach has the following often-quoted advantages; however, as part of the exercise, it is necessary to challenge this view – ‘Is it really an advantage or is it the result of dogma?’

- Different components can be worked on simultaneously thereby reducing throughput time, but is this reduction always true? It is worth mentioning that if the inventory between part and assemble sections is high, the throughput advantage is nullified. Also, is throughput time crucial, if you are making for stock or a long running product?

- Small bundles representing garments cut from one roll of fabric can be processed thereby reducing shading problems. Companies are reluctant to mix ‘shades’ in a bundle despite ‘batching’ the fabric and, most importantly, identifying each garment with a number system. If they do not trust the numbering system why are they still using it? If they do trust it, what are they worried about?

- In a factory layout, it is relatively cheap to implement the concepts and no major investment in handling systems is necessary.

The major disadvantages of this system, however, are:

- Effective material handling methods cannot be deployed, thereby reducing the operator’s performance and increasing the work content of the garment. Operators cannot work automatically and their rhythm is broken.

- Inevitably, garment pieces are lost as the bundle progresses through the line, and many supervisors do not worry about finding the missing component of the garment. However, if they have hourly output targets to meet and cannot move twenty-five or thirty garments because one sleeve is missing they will quickly readjust their attitudes and track down the problem parts.

- It is not easy to use ‘bundle tickets’ or ‘labour cost control systems’ when garments are going through the lines, two or three at a time.

- The retention of pressing quality is hindered, as garments are not hanging.

Alternative line layout options

There are two major alternatives or a combination of both. The first is the deployment of an overhead hanging chain or delivery system. There are many companies offering these and readers are undoubtedly familiar with them. Depending on the version used, they will deliver components to the operator in an easily accessible form, keep the work area tidy, improve visibility and consequently accountability, and more crucially preserve garment- pressing quality. The major drawbacks are cost and the need for competent production management to monitor the workflow!

The second alternative is to use a UPS system with trolleys, as a material-handling medium. This system is very effective in a jacket factory. Its chief advantage is that it enables sufficient pieces to be worked on by the operator while maintaining rhythm of work, relative low cost and flexibility- all the garments travel together, thereby eliminating the need to store and collate components. The major disadvantage is an ineffective use of space and the bulk of partly completed jackets since they are impractical for assembly operations. A suitably designed trolley will also act as part of the workplace layout, by reducing the operator’s need to handle garments. A bundle of 20 garments will allow the operator to lay out the work and operate with a good rhythm in an automatic manner. The exception to this approach is collar assembly where it is possible, because of their size, to work from the ‘block’, thereby maximising benefits of automatic working and workplace layouts. Completed collars will then be placed in bundles in the trolley prior to their issue to the lines. When the garment or component becomes too large to handle on a trolley, it can be transferred to a simple overhead chain facility and progressed with all components together through to completion.

Advantages of alternate layout

The above mixed practice has the advantage of allowing the operator to lay out ergonomically and work on a number of pieces, thereby encouraging rhythm of work. Many companies take a different approach and work with single garments on chains from the beginning of the manufacturing process to its end. The advantages of reducing collation, throughput times and work in progress (if the management has adequate line balancing skills) have to be weighed against the loss of rhythm and the extra costs incurred by installing additional chain supplied workstations. Work trolleys usually cost less than chain systems but there are a large number of overhead systems ranging from simple manually pushed hanging transports to the sophisticated and expensive computerised ones that we are all aware of.

Individual workstation layouts

Many machines come with built in equipment to help the operator. For example most pocket vent machines are equipped with automatic unload and stack facilities. It is therefore preferable to use fronts in ‘block’ to enable the operator to work with the machine and not have to stop moving every two or three pieces to complete the work. (It is not uncommon to see instances where managers have disabled the ‘auto-stack and dispose’ systems on machines, to enable working on single garments!). However, where machines do not have any built-in work aids, it is relatively simple to help the operator, with a degree of thought and a little investment.

As previously emphasised, the operator needs to pick up and load the component(s) onto the machine foot and then discard them with minimum of effort. With experience, they will lay out their work as best they can to achieve this. However, they can only work with the facilities provided to them. The work needs to travel as short a distance as possible, i.e., to be stored as near to the needle point as practical and to be picked up so that it can be immediately loaded onto the foot in the direction it is needed to travel.

It is emphasized that the operator should not have to learn from experience but should, as part of his initial training, be instructed on the ergonomic use of workplace layout and adherence to correct handling methods. The training of these procedures does of course assume that trainers have been correctly trained and are able to both recognise and utilise good workstations and sewing movements and also effectively instruct their charges.

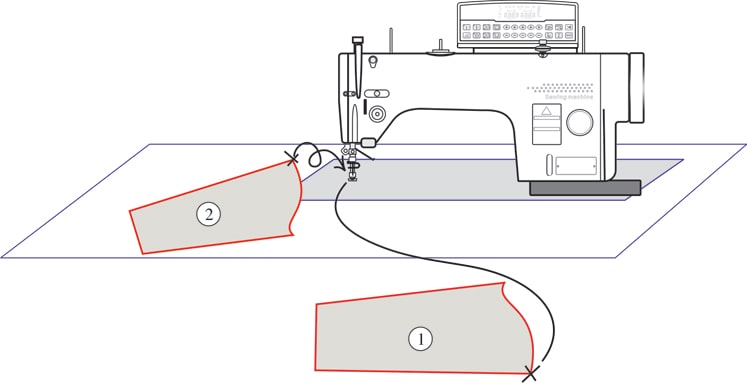

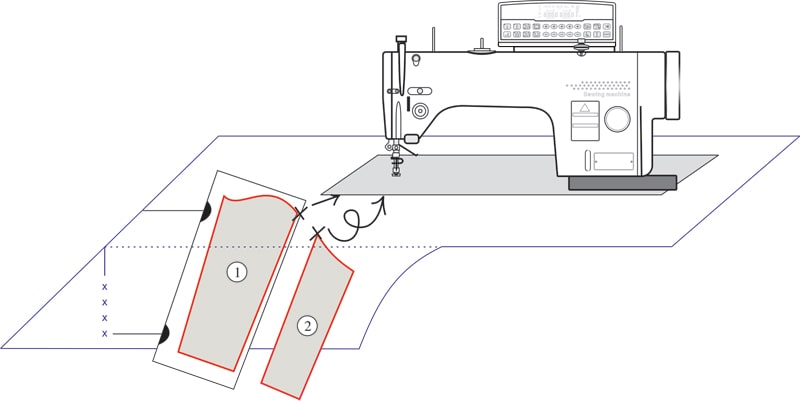

For example, let us consider joining the first sleeve seam (Fig1). Many operators will store one component (1) across their knees and the second (2) on the machine table. Component 1 needs to be grasped, lifted, turned through 90 degrees and placed on the machine table. Component 2, if placed incorrectly, needs to be turned through 90 degrees, aligned with component 1 and then placed in the foot. The operator because of a lack of facilities cannot store both components on the machine table. However, a simple extension to the table and a shelf would enable both components to be stored close to the needle, picked up simultaneously and moved quickly to the needle. (Fig 2)

Additionally, any collar operation can be significantly improved upon by storage near the needle and improved disposal facilities. Many operators leave collars in a chain and then cut back or attempt to dispose them onto the machine table leading to subsequent problems when the stack of collars collapses. However, cutting a chute in the bench and inserting a simple wire cage flush with the bench would enable a one-handed slide disposal- dramatically reducing work content!

Also, if bundles are being used, the production system should allow bundling to be of a minimum and completed in the most efficient manner (Velcro straps!). The customer pays you to produce a garment, not to tie bundles! During investigations in factories, I have discovered operators using up to 12% of their time untying, tying, taking work coupons and laying out components! Even a study of how the cutting room assembles the components in a bundle, can lead to savings. Small pieces are often placed inside larger panels to protect them from loss, but in most instances, it is the small pieces that need to be worked on and therefore accessed first!

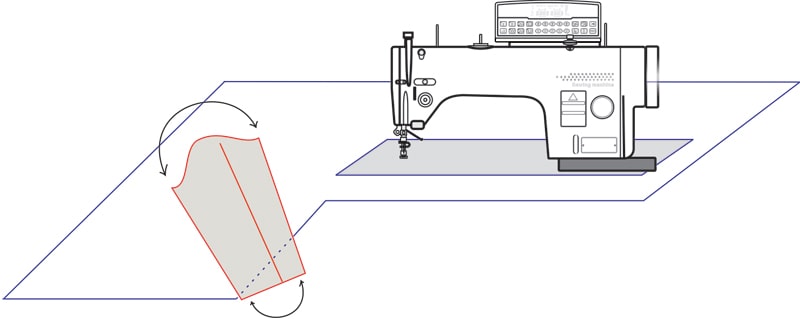

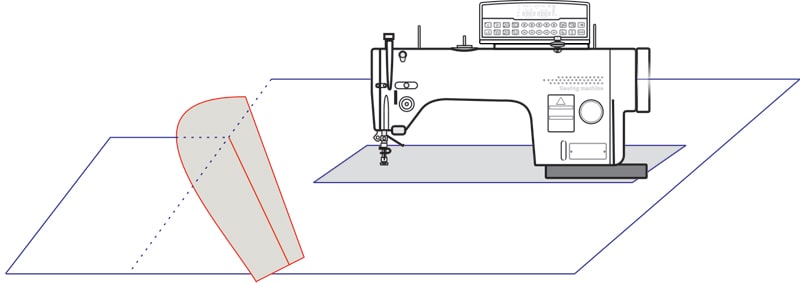

When assembling two-piece sleeves, it is possible to join the underarm seam and form vents with the sleeve lying flat in a trolley system (Fig 3) or with the sleeves lying on the machine bench or partly on the trolley top when it is included in an integrated workstation (Fig 4). They will become bulky when the second sleeve is joined as they can no longer lie flat and are therefore required to be hung on chains prior to joining of the second seam and preferably before pressing of the first seam and vent.

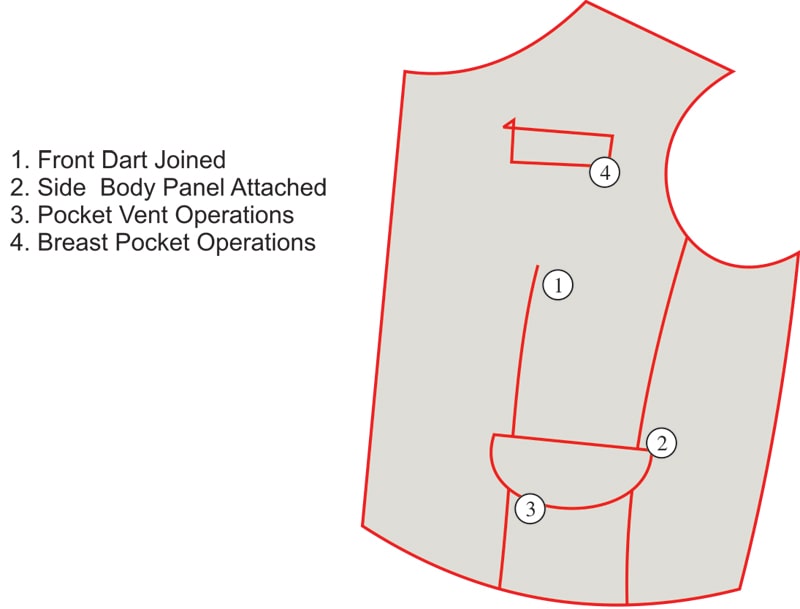

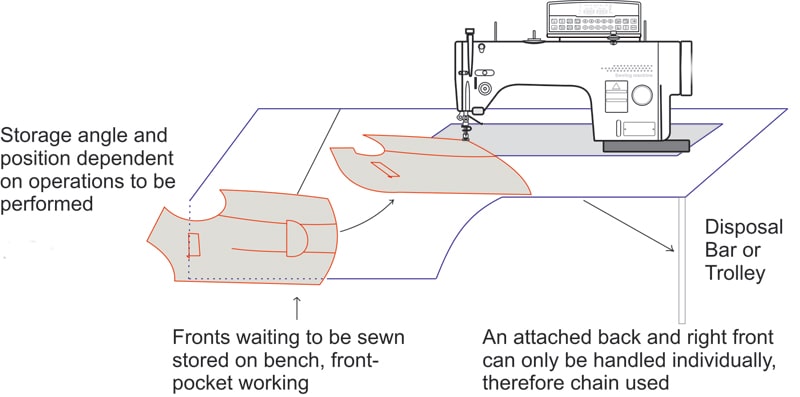

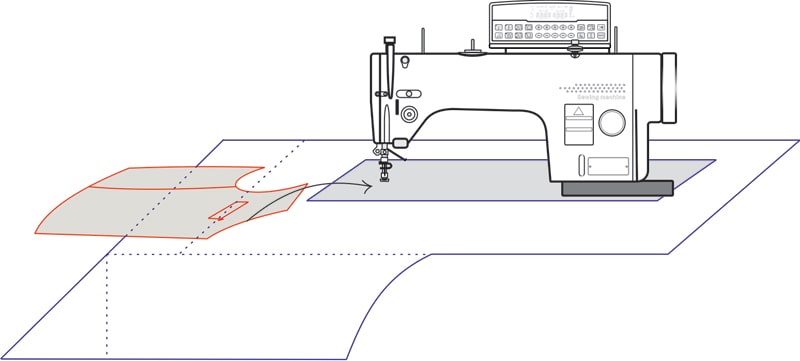

Similarly, a jacket front (Fig 5) will be readily manageable with a side panel attach, side pocket form (using auto pocket machine) and complete and form chest pocket. All operations can be completed with fronts stored on the machine. The storage angle and position is dependent on the operations to be performed (Fig 6). Such an arrangement also facilitates one’s working on the breast pocket (Fig 7). Thereafter, the front would need to be loaded onto a chain prior to pocket pressing.

Conclusion

All apparel entrepreneurs share a common characteristic, that of maximising production through the efficient use of the three M’s – Manpower, Machinery and Material.

The humdrum of daily routine seems to lull the manager into accepting the existing practices without challenging them and seeking answers to questions like, “Why are we doing that and is it necessary?” and “Is there a better method to do it?”

The menswear manufacturers have generally been considered to be the most traditional in the apparel industry. Paul Collyer seeks to change this conventional mindset by highlighting some of the problems commonly faced by the jacket-wear manufacturers and by providing practical solutions on how to make the best use of the factory and workplace layouts inviting them to review the existing practices in their factory and workplace layouts so as to get the best out of the system.