Improvising the design of the workplace of a sewing operator through a systematised ergonomic methodology improves the operator’s productivity and quality to a great extent. Keeping this in view, this article elaborates on the step-wise processes to be followed to change one’s existing workplace into an ergonomically designed workstation to reap in enhanced benefits in the work methods and production system. This article is by Horst Henning, the Chief Consultant of PFAFF Industrie Maschinen AG and a specialist in apparel and garment production techniques.

Before a project team or internal consultant starts looking into an area or individual workplace, we must follow the systematic approach and divide the action into three steps. Even when changing or rearranging parts of the production, we must always regard this as being a working system. Nothing is worse than having two or three members of the management standing around an operator and making comments about what must be improved. When the steps of the project have been decided upon, the operator must be informed of the possible changes. This will help to improve the chances that the operator will cooperate when the changes are implemented.

Step One: Documentation

A documentation of the present situation is a vital part of any changes. The team must observe the individual parts of the project and analyse each part separately before making the new proposal. The parts can be defined as:

- Arrivals: How the pieces come to the workplace?

- Machine: The function and degree of utilisation of each machine operation.

- Surroundings: All possible disturbance factors.

- Work Task: Check each movement of the production to see if they are necessary.

- Operator: Each movement and area in which the operator works by productive element.

- Departure: How the parts leave the workplace or working area?

With this ‘documented’ background information, see how each element fits to the change. The whole operation can then be analysed together and new ideas generated to improve each step. Next the ergonomic vulnerability of the workplace is evaluated as experience has shown that unwarranted disturbances in the human movement consumes extra energy as a result of which performance drops sharply after 5 hours. This is because the operator uses up the day’s energy in the first 5 to 6 hours, and can only work at 50-60% for the rest of the shift.

Step Two: Method Engineering

To find weak-points in the present system, we can use the conventional time finding methods such as stopwatch, multi-movement study or MTM (Methods Time Measurement). For this purpose we can use the following check-list in an adapted form:

Pickup (loading)

- Does the operator have all the necessary work information before she/he starts?

- Are the pieces to be sewn as close as possible for pickup?

- Are the pieces to be sewn in the correct sequence for sewing?

- Are the pieces positioned with the side to be worked on closest to the operator?

- Is it possible to pickup the pieces at the most convenient point to avoid repositioning?

- Is it possible to avoid bending and body twisting?

- Does the operator know all the possibilities to make the operation easier?

Processing

- Can the sewing or other activity be performed in a flowing motion without stops?

- Is the chosen method really the best possible one?

- Are the body movements the most rational for any of the operations, and can they be done without causing unnecessary fatigue?

- Can the body movements be performed without hindrance?

Disposal

- Is the disposal of the sewn piece as short as possible?

- Are the disposed parts positioned, so that the following operation can be performed rationally?

- Is the disposal possible with a sweeping movement?

- Do the disposed parts remain on or in the transport device?

If rationalization is to be carried out purely on individual operations, we must first make an analysis of the present methods and conditions. Once the planned changes have been agreed upon, we can start making the first trials. Changes should always be tested first. The operator must understand that the first change is not necessarily final and that corrections and adjustments will follow until the desired results are achieved. It is important to set a time schedule with a limit for the changes. This time limit must be known by the operator and all others involved. Furthermore, the whole project should be planned with a time schedule for the completion of each step.

Setting targets for the completion of the reorganization of the production for each operation is the next step. The new methods must be coupled with the new workplace engineering. In most cases this is a must and the operator has to be instructed by a trainer as to what she/he must do with the new workplace. A short interview and explanation can be very motivating. The individual needs of the operator can be learned and where possible, taken into consideration. Unfortunately, this procedure is often underestimated and neglected. The psychological impact on the operator of having lesser time than before to perform the operation can be positively influenced by the personal discussion. The company’s aim is to rationalize and have a return on investment that has been made in new workplaces.

Step Three: Review the Workplace Engineering

Machine Frame, Table and Stool

- Is the sitting position ergonomic?

- Is the stool height and position adjusted for the operator?

- Is there enough space for free movement of the feet?

- Can the operator operate the pedals ergonomically?

- Does the pressure needed to press the pedals suit the operator?

- Is the work table suitable for the parts to be sewn?

- Does the operator know about all the available work aids?

- Can the operator move her arms without fatigue?

Pickup and Disposal Shelves

- Are the number and dimensions of shelves adequate for the quantity and sizes of the parts to be worked on?

- Are the parts to be processed positioned properly to minimize the physical effort?

- Is the necessary physical effort so arranged that compensatory movements are used?

- Are the supplementary shelves positioned in the correct distance and height to the operator?

- Can the pieces to be worked on arranged according to the waterfall principles?

Linking and Auxiliary Apparatus

- Is there suitable transport to bring the goods to and from the workplace?

- Is the transport suited to an ergonomic picking up and disposal of goods?

- Can the workplace be freely engineered in conjunction with the transport system?

- Are all the auxiliary implements complete and fully functional?

Flexibility and Workplace Engineering

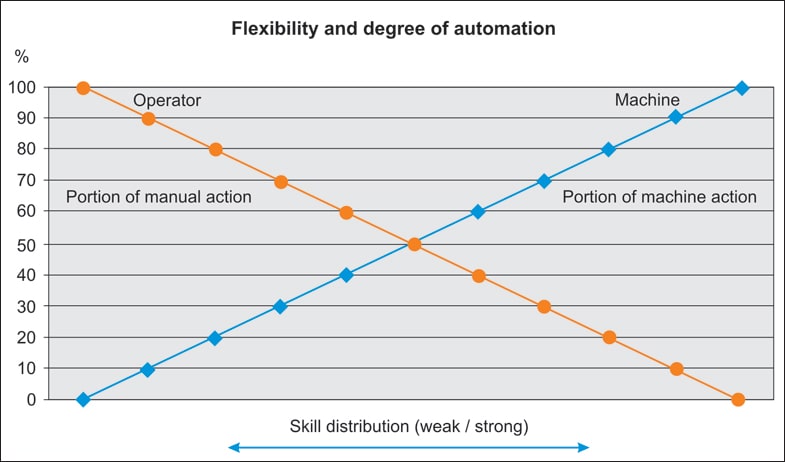

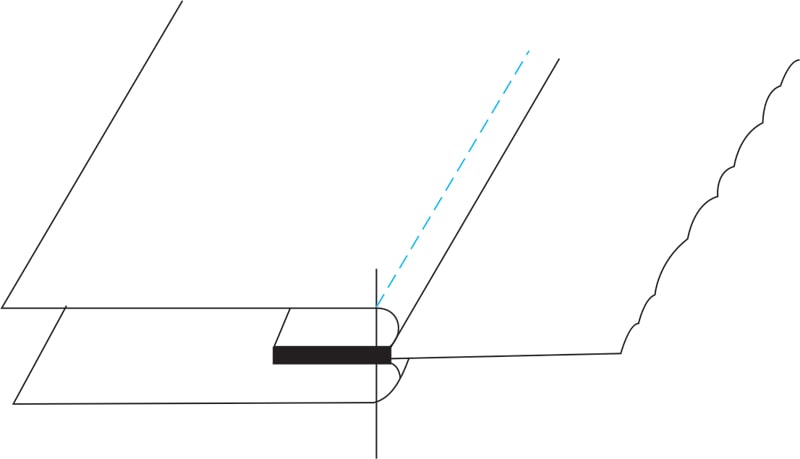

One aspect of any change in the workplace is, to achieve a greater degree of flexibility. Many operations in the garment industry have to be adjustable to fashion. This is very much so in the sewing of pockets. With the exception of a modular construction of pockets, the pocket setting workplace must be kept flexible. The higher the flexibility, the higher will be the utilisation of the workplace. Quick change folders and edge guides along with mechanical sophistication can be of great advantage (Figure 1).

Generally, when more flexibility is required, we need more operator proficiency. This means that if we raise the degree of automation, we restrict his flexibility. On the other hand, the more continuity we have in the product, the better we can rationalize the operator’s proficiency and save time while having a more consistent quality. When the operations to be reorganized have been analysed, we should see which of the operators need more flexibility. The team member responsible for these operations must plan to have the operator familiarize with the modular system. Under modular system it is advisable to use diverse interchangeable pickup shelves for various sized objects along with complete table tops that can be changed with a few quick hand movements to adapt to the new working conditions. It is not necessary to change the machine with table as the table top can be removed and a new size top fitted using a standard fixing system. The flexibility requirements are optimum performance, ample space and free movement area.

Sewing Table Shape and Workplace Engineering

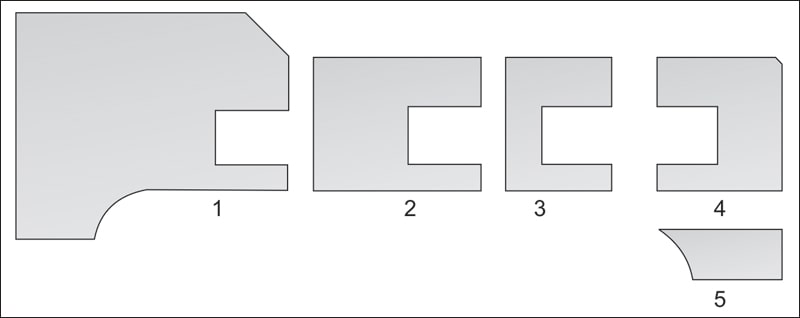

Even though more than 95% of the sewing machines used in ordinary factories are rectangular in shape and of standard size of 21 inches X 42 inches, the shape and size of worktable plays an important role in WPE. Figure 2 shows a range of possible table top shapes that could be used. Of course there are a multitude of different shapes that could be thought out and implemented. The size should be based on the standard table measurements for the country in which the production is situated. In the following sketches, table-top #4 is the basic part that remains fixed to the workplace, while #1-2-3 and #5 are interchangeable.

It is difficult to quantify the rationalization effects achievable through the table-tops, but it is significant. The advantages, especially in fashionable exclusive lady’s wear are high. When the quantities increase, we can use fixed table-tops that have been designed for the standard operation, to great advantage.

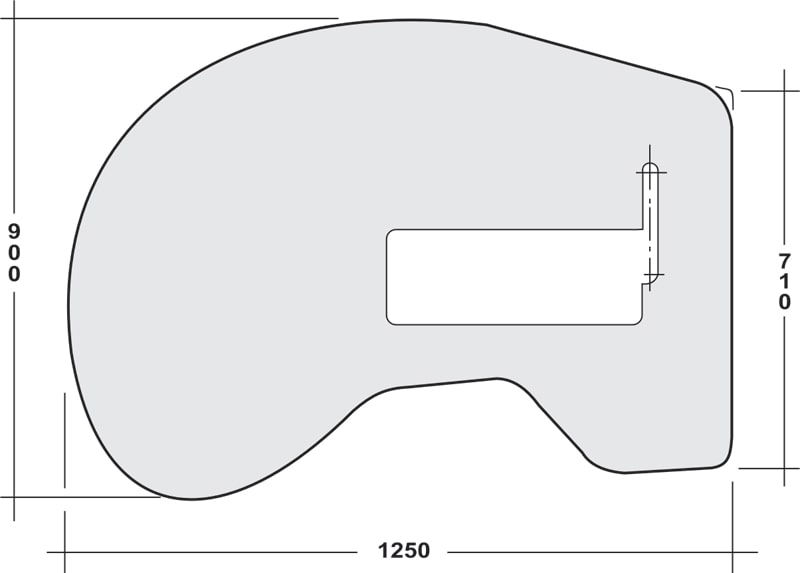

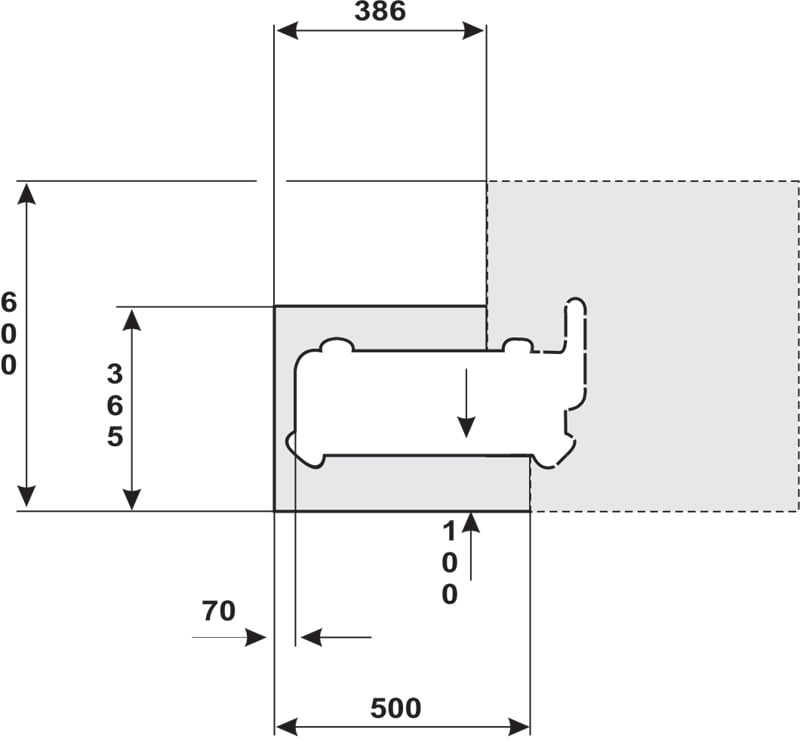

The example in Figure 3, shows a workplace that requires lot of handling space to support a large garment. For example attaching sleeves to men’s jackets and coats using trolleys as means of transport, The second example (Figure 4), shows a raised, shortened table, where skirt or blouse hems are sewn in a overhead hanging material handling system. It is important to have the edges on the left hand side of the shortened table rounded to avoid pieces from getting jammed and damaged while passing. The modular system can normally be recommended if the machine head is required intermittently at different operations. The difference between the modular, flexible system and the fixed tables lies in the requirements of the factory and the production quantities. The fixed system requires continuity without constant changes in the operation.

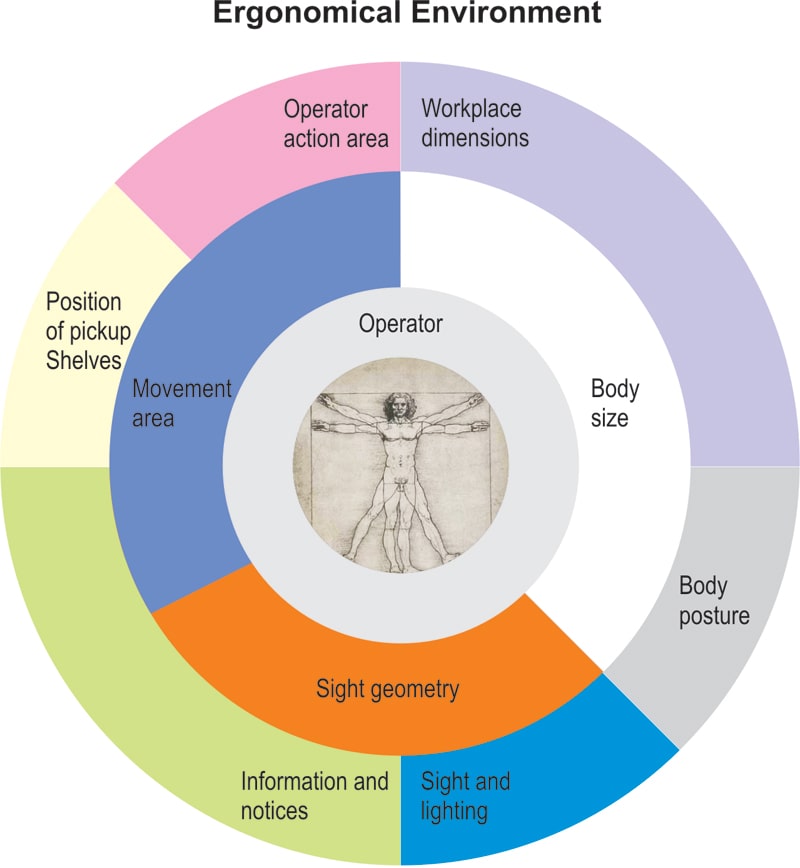

In some cases, while engineering a workplace, we get the impression that the operator is unhappy with the changes. This can happen in cases where the operator is not convinced that the changes are also to her advantage. There are no standard solutions for this problem. Basically, the workplace engineer should keep the needs of the operator in mind when designing an operation. In the garment industry, the handling at the workplace takes up about 75% of the operation time. This fact shows us how important the operator is in the production process. The operator should always be the centre of workplace, as in most cases, she must achieve the new targets. The human and physiological points are important. When changing single workplace elements, we must see that the height of the stools, machines and pickup shelves are adjusted accordingly. In cases where the present operator is replaced by another, we must expect a different geometrical setup. Each workplace must be adjustable to size of the individual operator if we want to get the best performance from the operators. This is also true of the other spheres depicted in Figure 5. The operator is and will always be kept in mind if we want to reach our rationalization targets.

Example of a WPE

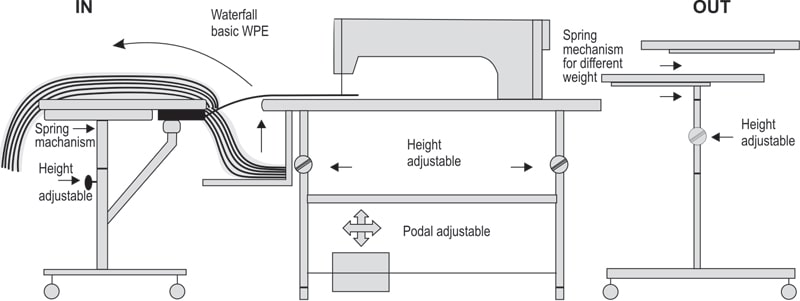

The following example (attach yokes to shirt back with single needle machine (Figure 6), shows what an optimised workplace could look after a reorganisation. The basis is the seam which is a necessary part of the construction.

The seam sketch in Figure 6 is the requirement of any technical solution for man and machine. In this case the methods are dependent on the degree of investment involved. Generally, the more complex and sophisticated a workplace becomes, the more necessary it becomes to develop the methods accordingly. This is not always the case as we develop the methods either for operator simplicity, with more machine presence, or to a higher skill of the operator.

In the following example (Figure 7), we have put the emphasis on the optimal space/area at our disposal. Further, we assumed that the maximum quantity of shirts to be produced would warrant the investment. To the left of the operator, we find a height adjustable pickup shelf with a clamping mechanism. The pickup and disposal follow the waterfall principles, in this case from top to bottom. (The disposal direction is indicated by the curved arrow.) The pickup shelf can be spring controlled so that a fully trained operator can pick up from the same spot without looking, as the height is automatically adjusted by the weight. The same applies to the pickup shelf on the right side where the yokes are stored. The shelf under the left side of the machine table should also be height adjustable. By doing this we can cater for various thicknesses and weights of cloth.

When compared to simple solutions for the same operation in the industry, we can save up to 30% in costs. If the previous method was attach, turn and topstitch, then the savings are nearer 50%.